Gypsies and Jews

Gypsy stereotypes might beget stereotypical gypsies. Is that why Jews are so successful?

This was a timed post. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. You can find my previous timed post here.

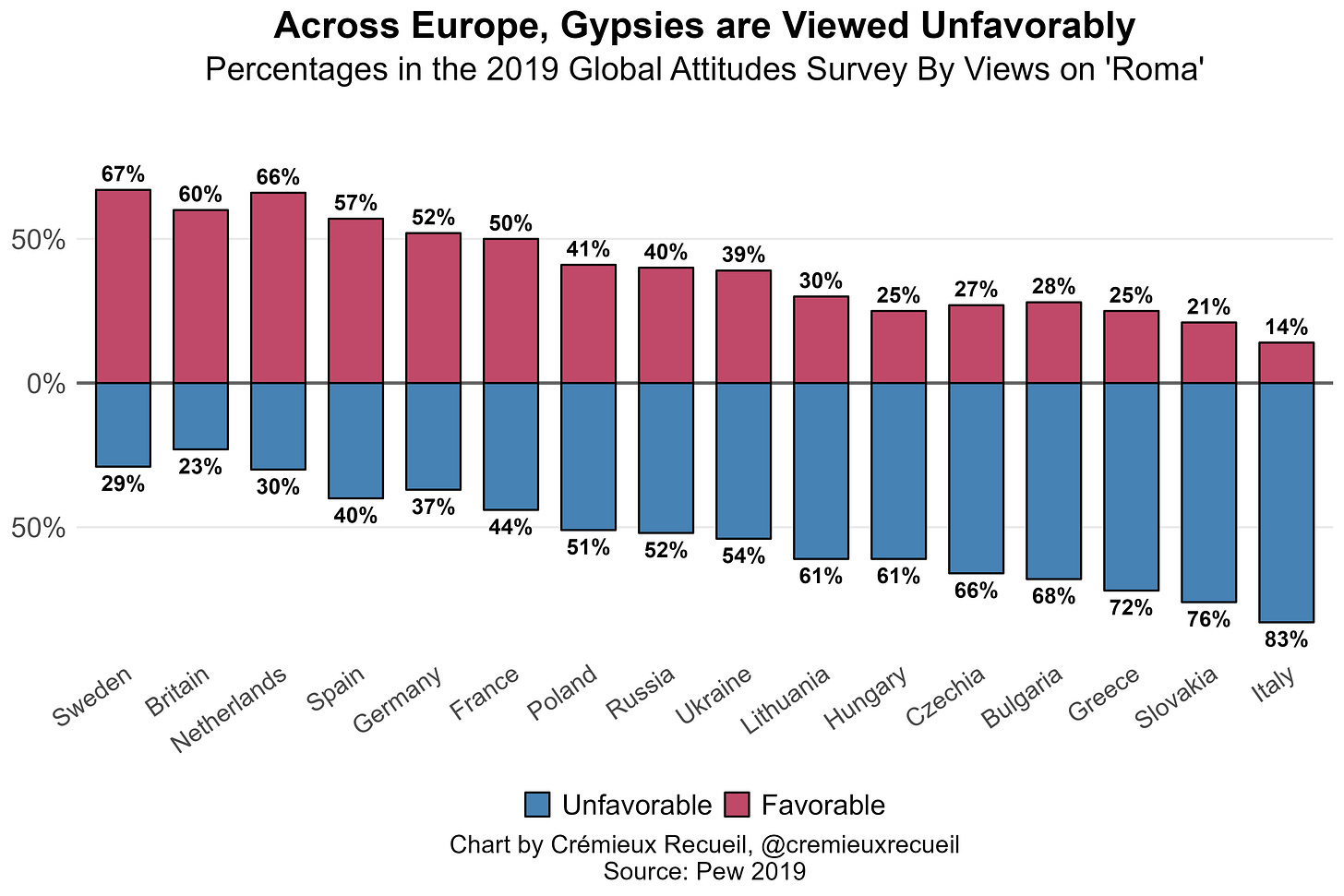

The received wisdom in most of Europe is that gypsies suck. Polls and Eurobarometer discrimination polling support this. The people who live in countries with sizable gypsy populations do not tend to like gypsies, whether they’re called gypsies, Roma, Romani, or some more specific term like Sinti, Manouche, or Kalo.1

There’s something to this disdain. Gypsies are heavily overrepresented in crime, and like many groups that are disproportionately prone to criminal behavior, they’re low-class, not just in terms of being poor and uneducated, but also in terms of engaging in a bundle of unappealing cultural practices.2 But what if the reason they’re perceived so poorly is because they’re perceived poorly?

Imagine you were born into a group that everyone loves to hate, a group that’s targeted for discrimination, that could easily and plausibly become self-loathing because of the perceived acceptability of just hating them. That could very well be daily life for gypsies. Accordingly if a gypsy is able, why not identify as something else? And if enough willing and able gypsies identified as something else, what would that do to the gypsy population? That is the subject of a new paper by Mitrut et al.

The authors of this paper had access to Romanian administrative data covering millions of Romanians. This data includes self-reports on individuals’ ethnicities, self-reported over several years. With this data in hand, the authors could check whether people persisted or desisted in identifying as members of a given ethnic group, such as gypsies or Romania’s more prominent minority ethnic group, Hungarians.

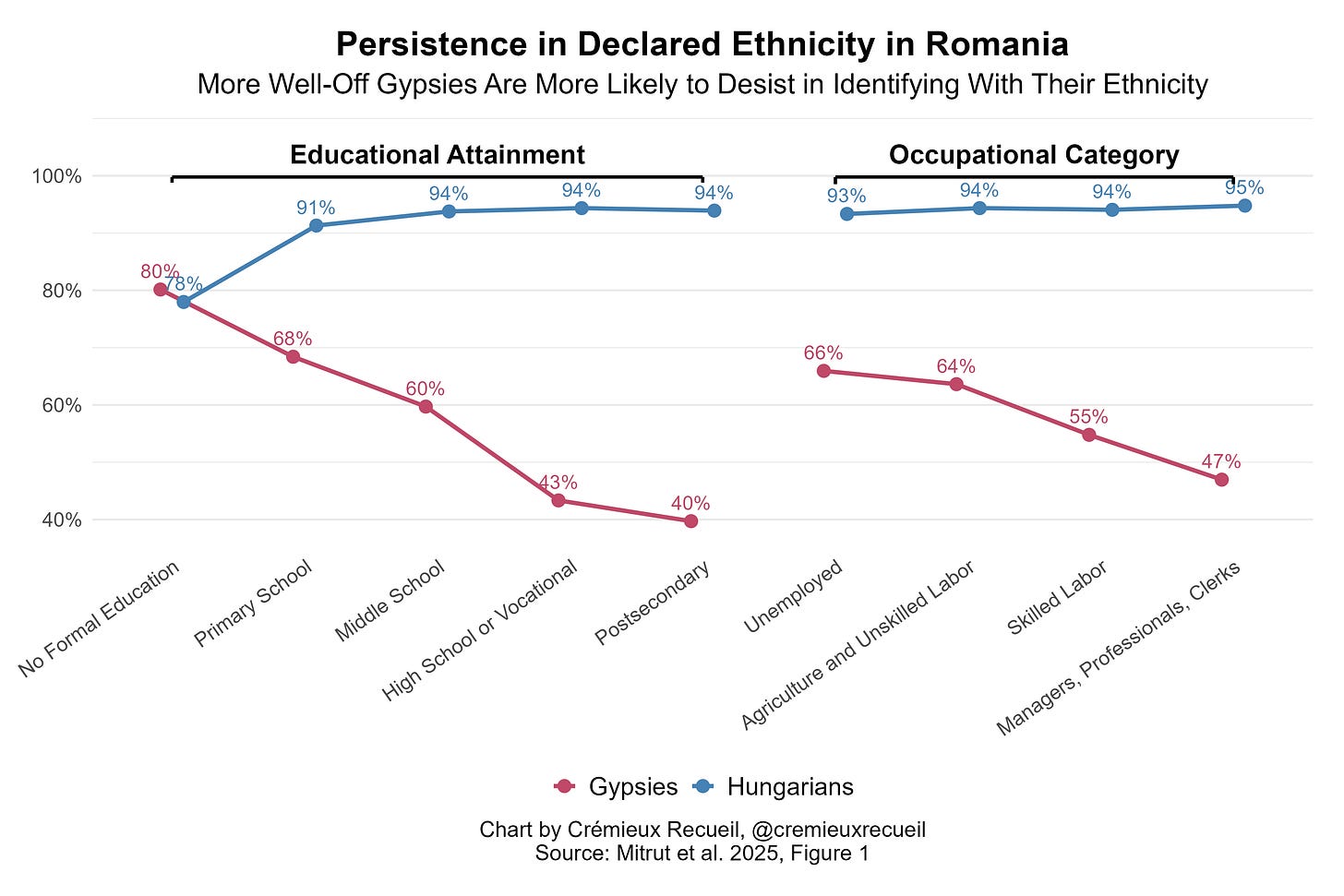

In order to get at true desistence in ethnic self-identification, the authors assumed that the unintentional mismatch rate was twice the self-reported rate of inconsistent reports of one’s sex. With that in mind, take a look at how often gypsies desisted in reporting that they identified as gypsies, and compare that to Hungarians:

The key detail here is that gypsies selectively desist in identifying as gypsies. Those who advance in the educational system are more likely to stop identifying as gypsies; those who move into higher-paying, more prestigious jobs are more likely to do the same. In fact, more than half of gypsies who become professionals change the way they identify themselves, they claim that they’re members of some other ethnic group.

The scale of this attempt at passing as something else is enormous. The implied numbers of gypsies in Romanian society is far higher than self-reports suggest, but the greatest underestimation of gypsy numbers takes place at the highest levels of Romanian society. In fact:

[We] find that there are more than twice as many Roma-heritage high school graduates, and 1.5-2 times more middle school graduates, primary school graduates and Roma without formal schooling. For postsecondary graduates, there are roughly six times more Roma-heritage than in official data, when the shape of individual heterogeneity is normal or uniform… Because it is impossible to learn about this group of people using our data, we also report estimation results using the lognormal distribution…. This is our most conservative specification, and we find there are 2.7 times more postsecondary graduate Roma-heritage individuals.

In absolute terms, there are roughly 275,000 more adult Roma-heritage individuals than reported Roma at the 2011 census in our matched sample. This means that within our matched sample, the proportion of Roma-heritage in the Romanian adult population is roughly 3.7%-4.1% of the total Romanian population, rather than a reported 2.3%. In terms of educational achievement, we estimate that Roma-heritage adults completed 6.2 years of schooling, versus 5.8 years for reported Roma.

The authors followed this up with a survey involving 2,000 Romanians across the country. They wanted to know if they thought gypsies passed, and how they passed, and in order to get a decent result, they provided them financial incentives if they provided correct answers. Most did not provide correct answers. That is, they misunderstood the nature of gypsy passing: they were more likely to think it was something for less educated rather than more educated gypsies.

Respondents also tended to claim that they could tell if gypsies were trying to pass, but the things they considered ways to determine if someone was a gypsy were not things that would be good at identifying gypsies. Romanians believed that they could identify gypsies from their clothing—which is easily changed—their physical appearance and skin color—which, though it will upset many Romanians, substantially overlaps with their own—their names—which are actually not very distinct from those of other Romanians—and, primarily, by how they spoke.

Given the combination of Romanian ignorance about gypsy passing and that the gypsies who appear to try to pass are the most capable ones among them, gypsies can probably pass as some other ethnicity successfully in Romanian society, and it’s likely that they do.

Accounting for gypsy passing “explains roughly 13% of the Roma-non-Roma education gap.” It also plausibly contributes to stereotypes of gypsies, because the ones who keep identifying as gypsies are less elite than the ones who stop. In other words, what Romanians know and dislike about gypsies, the low-class stereotype… it may be true, but it’s less true than they tend to know, because high-class gypsies stop identifying as gypsies and Romanians don’t know it:

If the passing patterns observed in official records extend to everyday social and professional interactions, our results have deeper implications. The strong positive educational gradient in passing, coupled with the apparent lack of awareness within the general population, suggests that passing may reinforce existing negative stereotypes about Roma. Indeed, to the extent that stereotype creation and statistical discrimination is partly based on observational learning, the relative lack of visibility of highly educated Roma may skew perceptions about the entire group.

Gypsies self-identifying as something besides gypsies can skew the statistics on, and maybe even real-world perceptions of, gypsies as a group. Perhaps the same thing might be true for other groups.

I’ve discussed several examples of phenomena like this before. Consider the concept of ethnic attrition. This is where immigrants stop identifying with their ancestral groups over the generations. A well-known instance of this is the large number of America’s English and Scots-Irish who now identify as ethnic “Americans”.

An example my readers will find more interesting is that of Africans. This is actually a major issue for understanding statistics about the descendants of African immigrants. For whatever reason, downwardly mobile descendants of African immigrants are more likely to identify as “Black” and not “African”, leaving us with assessments of African socioeconomic standing that are—in the words of one researcher—“unduly optimistic”.

Mexican Americans are quite the opposite: the less successful ones stick to the Mexican label in subsequent generations. Part of this has to do with intermarriage. Hispanics frequently marry members of other racial/ethnic groups, and the products of intermarriage are more likely to identify as something besides Hispanic. Consequent to the intermarriage, sometimes analyses of Hispanic assimilation (or the lack thereof) may misconstrue admixture and assimilation effects. But I digress.

There are many processes like these that change group identification and artefactually move around the status levels associated with different group labels, without really affecting any sort of underlying status distribution given we had a full picture on the identities of the groups in question. And while that’s not really interesting since it’s just a data completeness problem, sometimes processes like these are even more interesting. Sometimes these processes modify groups and make them distinct.

The story of Jewish success does not start in Europe. European Jews are the Jews whose success is most well-known, it’s true, but that success would never have been possible without Jews already being formed into an elite long prior to entering Europe on a meaningful scale. In fact, Judaism’s ‘golden age’ occurred in a place, and at a time, that would surprise most people: in the Muslim Middle East between 800 and 1200 AD.

This story comes via Botticini and Eckstein in their brilliant book The Chosen Few.

It begins in ancient Israel, in the first century BC. The two dominant Jewish factions at the time were the temple-controlling Sadducees and the learned Pharisees. To spread knowledge of the written Torah, the Pharisees established networks of schools, and after the fall of the Second Temple to the Romans, they gained the authority and cachet to wrest control from competing factions. They used that control to institute an ordinance by which Jewish fathers were required to educate their sons on how to read the Torah.

Providing an education in the premodern world is, as it turns out, quite expensive. In Judea, most people were farmers and most farmers in the Malthusian (pre-industrial) era of the world existed on the edge of subsistence, eking out a meager standard of living. And yet, the norm towards providing one’s son with an education still spread, and it spread rapidly. In short order, and perhaps partly deliberately, that norm generated an outcast condition in the Jewish community, reserved for those who did not educate their sons. These were the so-called am ha’aretz, or people of the land.

The disdain for those who were themselves uneducated and those who failed to provide their sons with an education was so strong that it became standard rabbinical teaching to consider a marriage to a women who was the daughter of an am ha’aretz unseemly, since if the man somehow leaves the picture, his sons might be condemned to being am ha’aretz themselves. The am ha’aretz were so reviled that marrying one was considered to be like breaking kashrut.

This provided a wonderful opportunity for Christians to find converts. The am ha’aretz wished to maintain their monotheism, but to avoid the stigma and ostracization associated with illiteracy. So, the am ha’aretz—usually the poorest among the Jews—disproportionately changed faiths and became Christians, leaving behind a Jewish faith that, while still largely rural, was definitely occupied by a richer set of people, who would continue becoming richer so long as it was still desirable for the poor to filter off into others faiths.

This situation of the Jews changed with the birth and spread of Islam.

Compared to the Romans and the Byzantines, Muslims were fair dealers. They placed fewer restrictive laws on Jews, let them freely travel within the Muslim world, and discriminated against them far less than the Romans had, so long as they paid the head tax—the jizya. Those who could not pay the tax were obligated to convert to Islam. Thus, instead of flowing to Christianity—adherents of which also had to pay the jizya or convert3—poor Jews started peeling off into a new faith. The same was true of poor Christians.

Because the Muslims were generally fair rulers, we see the impacts of this in the modern day. At least before the establishment of the modern country of Israel, in most parts of the region, Jews tended to be wealthier than Christians, who tended to be wealthier than Muslims. What made the advent of Islam so interesting is that it made Jews far wealthier not just by peeling off poorer Jews, but by providing Jews with an outlet to ply literacy—and the mathematical and alternate language skills that came in the course of education—to make money with the skills cultivated under Roman rule.

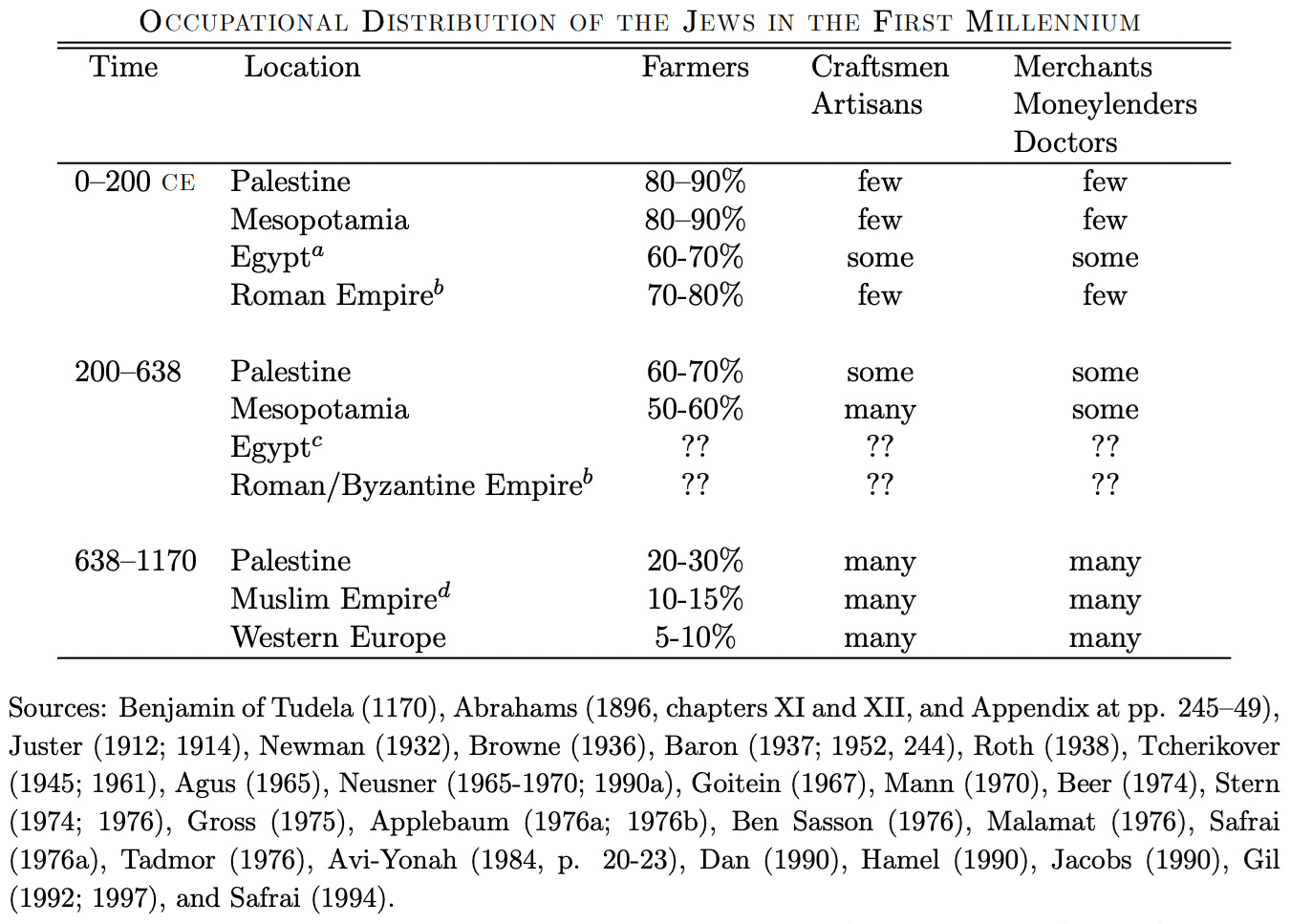

The reason for this has to do with Muslim efforts to urbanize. With the deliberate establishment of urban centers, suddenly there was a place Jews could go and become craftsmen, traders, and members of other skilled occupations. Jews also had faith-based advantages in these occupations beyond literacy, in the form of contract-enforcing institutions specific to Jews and relationships among Jews. With motive and opportunity, Jews went from being largely rural and farmers—like most everyone else—to being both literate and skilled:

From this point, Jews were socially established and the golden age circa 800-1250 began. And, as skilled professionals tend to do, Jews naturally began to seek out investment and business opportunities.

Jewish migration to Europe began with European rulers inviting Jewish families into their towns. Towns would sometimes even ask their rulers to let them invite Jews, because Jews could fill an economic niche Christians could not: that of lenders; craftsmen when there were few or none; traders when trading over a distance was difficult without arbitration mechanisms like Jews had; tax collectors when people didn’t want to, were restricted from, or could not be trusted to tax their own; and perhaps most impressively, royal treasurers, who would take a role in the intentional development of Europe’s own urban centers and communes.

Because the continent’s rulers restricted which Jews came into Europe, those who made it were naturally going to be more impressive than those who remained in the Middle East. And suddenly, those flows were abated, effectively establishing a rift between the Middle Eastern and European Jewish niches, within which Clarkian-style development propelled Jewish aptitudes further… thanks to the Mongols.

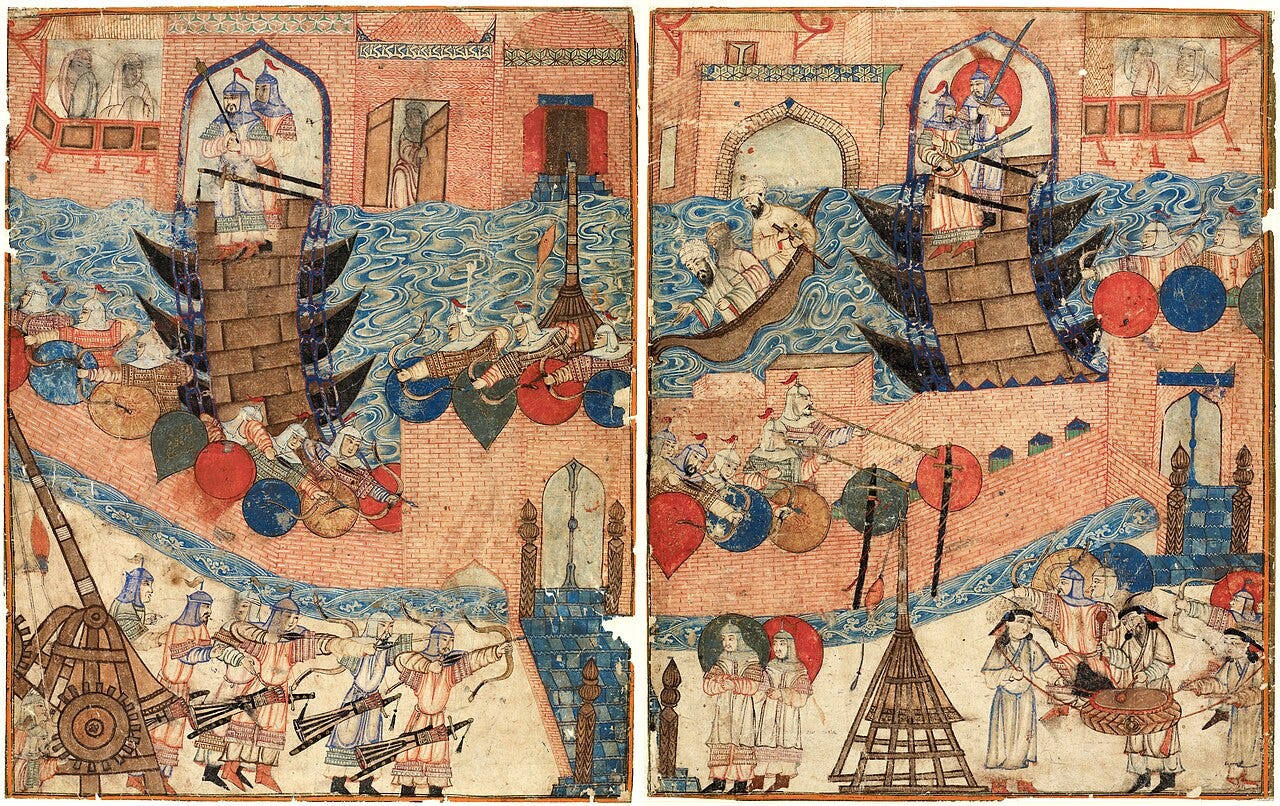

In a series of military campaigns, the Mongols devastated the Middle East. The invasions of Persia and Iraq in the 1250s ended the Abbasids and even pushed many among the Muslim world’s successful Jewish upper-crust into subsistence farming. This meant having to pay for education on a farmer’s budget in addition to the jizya, which was also frequently pushed up to a higher rate due to the suffering felt at the hands of the Mongolian invaders, adding additional pressures that cratered the size of the Jewish population.

The numbers in the Muslim world dwindled to so small a level that inflows into Europe became minuscule. At the same time, two of the largest realms in western Europe became closed to Jews, limiting the number of entrances onto the continent and pushing the locations of those on it eastward, where life was harder and realms were more fragmented. This was because of England’s Edict of Expulsion—motivated by Edward I’s desire to escape his debts—and France’s various similarly debt-motivated expulsions starting under Philip IV and continuing with his successors.

From here, the story should be familiar enough to many of you already, so I’ll digress.

The story of gypsies is like the early story of Jews in that it has a lot to do with discrimination. In the modern day, part of the process that makes gypsies look bad is selective de-identification with being a gypsy: smart gypsies filter out. In ancient times, part of the process that made Jews look good was selective de-identification with being a Jew: poor Jews left the religion.

The motivations of those involved in both cases were different and the effects on the groups after those decisions were made are certainly different. What runs through both stories is the immense power of selective group identification.

And I’m told that in countries like Spain, polled disdain for gypsies would be greater if pollsters asked about them using more familiar designations like “gypsies” instead of using the lesser-known term “Roma” in their polling.

Such as placing aluminum foil over their windows in new homes.

Or, in some cases, they could provide military service.

The Torah plays the largest role: because of the text, only in Judaism do we believe we can change G-d and His mind. Only in the Judaism do we believe that Good Works will change the future of the world. This mindset means that Jews culturally and instinctively understand that we can - and must - strive to change the world. That belief alone gives us the courage and risk tolerance to attempt what others do not.

While the current review accentuates slowly-working evolutionary pressure, I would like to stress that the Scripture actually describes (as a counterpoint) a within-one-generation extreme upward mobility. As one can see from the stories of Joseph in Egypt, Daniel, Azariah, Hanania and Mishael in Babel, or Esther, Mordechai, Ezrah and Nehemiah in the Persian Empire.