China's Upside-Down Meritocracy

New evidence suggests China systematically misallocates its human capital

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

This is the seventh in a series of timed posts. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. Check out previous examples here, here, here, here, here, and here. I placed the advertisement before I started my writing timer.

Warum Europa?

Mario Draghi’s recent report on the European Union’s competitiveness included multiple mentions of venture capital, venture capitalists, VCs, and the importance of venture capital for growth. Two of the more shocking notes from the report include:

In fact, there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years, while all six US companies with a valuation above EUR 1 trillion have been created in this period.

And, emphasis mine:

The huge gap in scale-up financing in the EU relative to the US is often attributed to a smaller capital market in Europe and a less developed VC sector. The share of global VC funds raised in the EU is just 5%, compared to 52% in the US and 40% in China. However, the causality is likely more complex: lower levels of VC finance in Europe reflect lower levels of demand…. Many EU companies with high growth-potential prefer to seek financing from US VCs and to scale up in the US market where they can more easily generate wide market reach and achieve profitability.

You read that right: Companies in the EU command a mere 5% of global venture funding versus over 50% for American companies. Because the EU has so much human capital, this obviously should not be the case. Europeans can innovate and they can found companies that are enormously profitable. We know that they have innovated and they will innovate in the future, and we know that plenty of them want to found big, successful companies, but European countries and the EU make it incredibly hard for Europeans in Europe to actually do these things at the scale Europeans in America are frequently able to.

This is a considerable part of why Europe, despite its human riches, has fallen behind.

Is Business Dying in China?

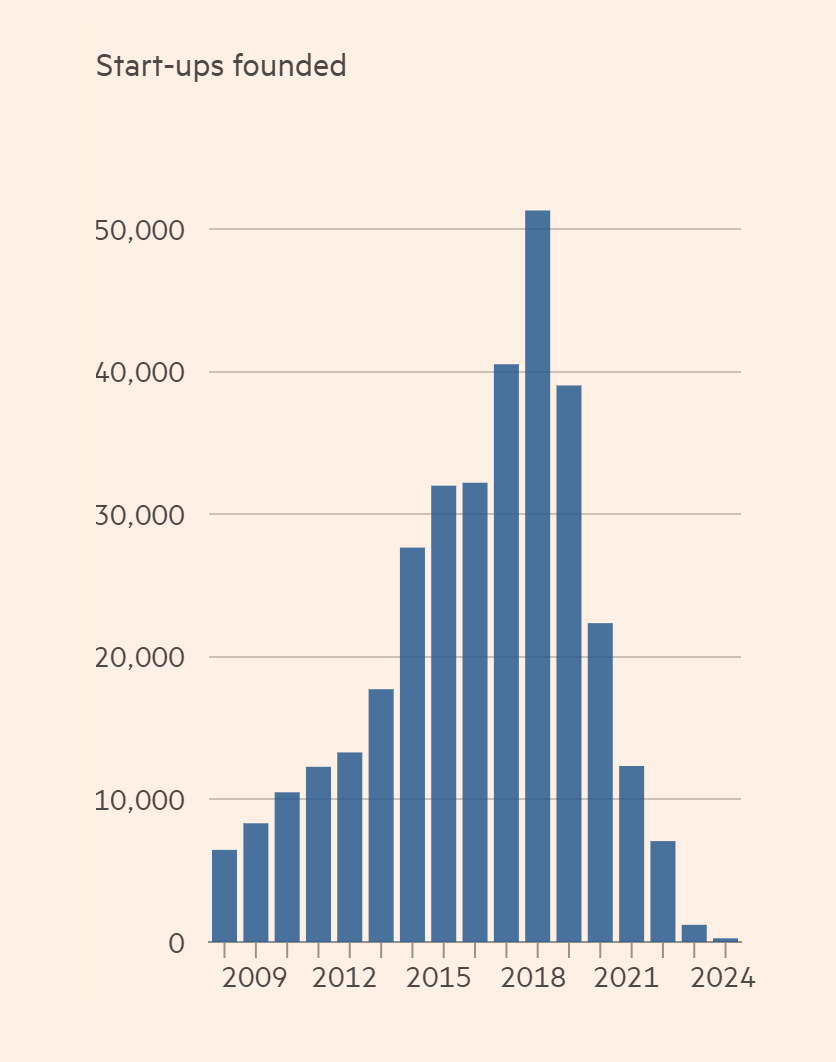

As in Europe, there are worries that China has developed major problems innovating and building companies. A recent Financial Times (FT) piece vividly illustrated the weight of these concerns with a plot that immediately went viral:

This chart has proved to be contentious, and the CEO of the company that produced the data has suggested that it’s inaccurate and, at the very least, in need of context.

For starters, the source of the data is ITJUZI, which is basically Crunchbase for China. One of the problems with using Crunchbase to assess new start-up numbers in an ongoing year is that many new companies are going to be missed. It might even take multiple years for them to make the list. The CEO of ITJUZI suggested that a recency bias might leave a lot of companies off of the chart and that ITJUZI being selective—like Crunchbase—could also impact the results.

ITJUZI being selective, you can probably tell that the chart doesn’t show what it appears to: it is not a chart of start-up numbers, it is a chart of a specific type of start-up’s numbers; namely, start-ups that appeared on ITJUZI by the time of the FT article’s analysis. In 2023, China actually saw almost 33 million new businesses established, just as America saw almost 5.5 million new business applications filed.1 All businesses might not be what you think of when you hear “start-up”, but it’s still important to note that the common misinterpretation that China’s business numbers cratered is unsupported.

Other users pointed out that fundraising amounts and the number of transactions for ITJUZI-listed companies have not cratered in the past few years, that while the mood for Chinese venture capital and private equity might be bad, those things aren’t synonymous with entrepreneurialism, that municipal governments have made some good calls supporting companies that would otherwise be VC-backed, and that the percentage of companies closing down recently has returned to normality after a number of U.S. venture capitalist departures from the country in 2023. Steve Hsu has even said that he’ll be talking to “one of the most prominent investors in China” about how the FT article including the chart above does not provide a realistic picture of the venture capital and startup ecosystem in China.

China Misallocates Top Talent to Government

Even if China hasn’t recently ravaged its startup scene—which it very well might’ve—, that doesn’t get it the hook. You see, China has a massive and highly-capable government. This means China is badly misallocating its human capital.

China’s top exam is the Gaokao, the Nationwide Unified Examination for Admissions to General Universities and Colleges. This examination is hard compared to standardized tests like the SAT and ACT, and the people sitting it tend to be a very selective bunch relative to China as a whole. Despite being a brilliant sample of the population, people still put in a lot of study in order to do well, and each year there are plenty of suicides over poor performance and anxieties surrounding the test.

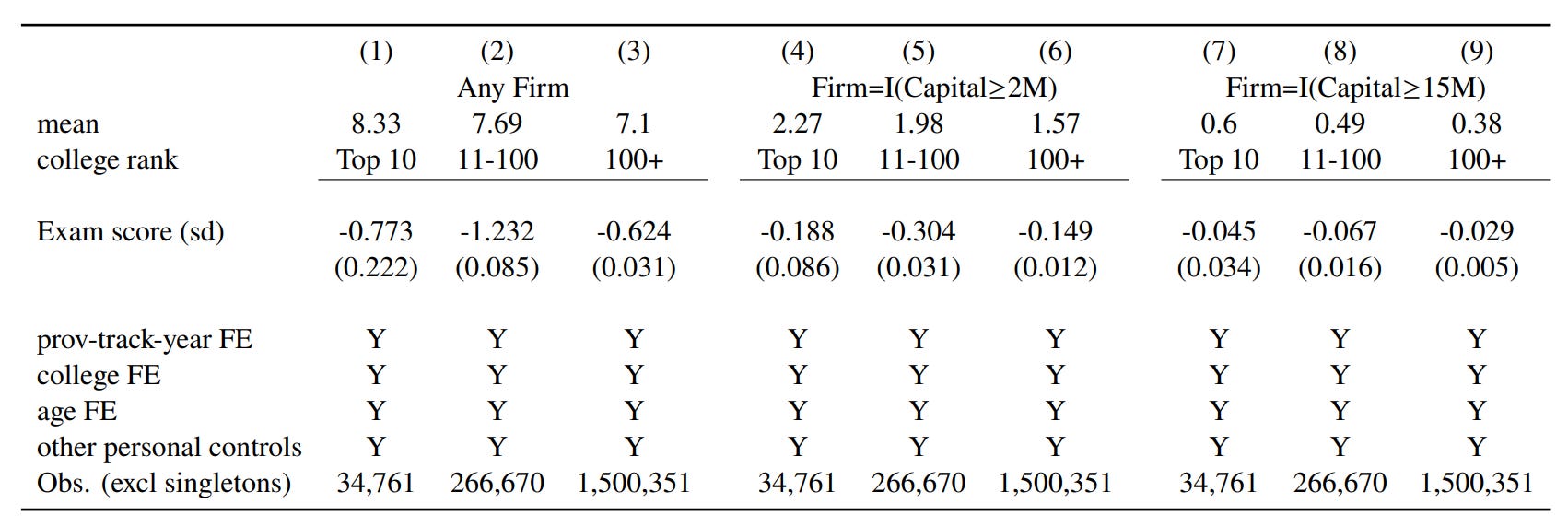

The real kicker for China is that, whereas in the U.S. and Europe2, and probably almost-globally, smarter people are more likely to start and succeed in business, higher scores on the Gaokao are related to lower odds of starting a business.3

This phenomenon is pervasive. The probability of founding a firm is higher for those majoring in economics, finance, and law than for those in the humanities and STEM. Just as well, the probability of founding a highly-successful firm, with at least 15 million RMB in registered capital, is higher for those in economics, finance, and law, than for those in STEM, for whom the probability is greater than for those in the humanities. Within each major, higher Gaokao scores are related to lower probabilities of starting a company.

Students at the highest-ranking universities produce more companies and more large companies than the students at lower-ranking universities, but across university rankings, once again, higher Gaokao scores are related to lower odds of founding a company.4

But, at the same time, higher scores on the Gaokao were nevertheless related to higher odds of businesses succeeding.

Both conditional on entry into university (as shown above) and not (see the paper), Gaokao performance is related to corporate success.5 Having higher scores is also related to founding firms that survive significantly longer:

Gaokao scores are significantly related to higher post-graduation wages, higher odds of obtaining a job that provides someone with local residency (Hukou), higher GPAs, more academic awards, and—revealingly—Communist Party membership. There are certainly major rewards to starting a successful company, but the simple and more frequently preferred route for highly capable Chinese students is to join the Party and work for the state.

China is funneling its best and brightest into government and that makes them weak.

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

And Then China Breaks Them

Government isn’t the most productive place to put the capable in any developed nation, and China is no exception. But China not only wastes talent in government, it actively pushes highly-capable civil servants to do bad things. One of the bad things China’s civil servants are encouraged to do is to lie.

In Chen et al.’s 2019 forensic examination of China’s national accounts, they described one way China’s government officials lie. Local governments in China report the data required to construct national accounts and the government rewards bureaucrats who succeed at hitting growth and investment targets, while punishing those who come up short. In line with those incentives, bureaucrats misreport, but the National Bureau of Statistics recognizes this and adjusts accordingly. This adjustment? Fine, until about 2008, whereafter the adjustments haven’t been sufficient because local governments have overreported by increasingly large amounts and the adjustments made by the National Bureau of Statistics haven’t kept up. The growth rate in China has therefore been considerably overstated.

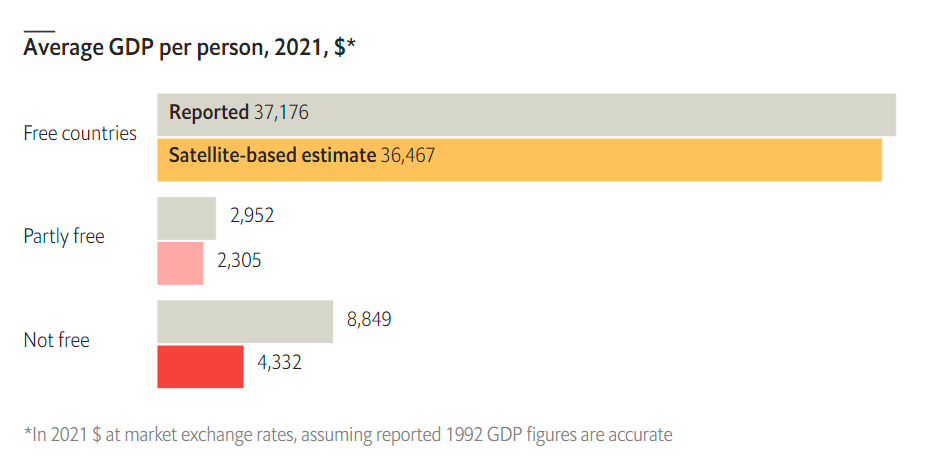

Others have confirmed the existence of this phenomenon, not just in China, but the world over. Using nightlights, we can see that GDP per person is generally accurately reported across free countries, but it’s highly discrepant in countries that are clearly not free, like China.

Looking specifically at China, it stands out as one of the worst misreporters:

Lying about the figures used to estimate GDP is a familiar and, by now, well-worn example of China’s governmental incentive problems.6 China’s bureaucrats also act stereotypically, consuming out of the public purse, because they might as well. This corruption literally makes them fat because they use public funds to buy alcohol and luxurious food. When anti-corruption initiatives started in 2013, China’s ministers quite literally got skinnier:

One of the more interesting examples of how China’s ministers are incentivized to act badly comes from its patent indigenization campaign. For background, China’s highly-centralized government frequently embarks on revolutionary-style campaigns in which the nation’s leadership pushes the country to work towards one overarching goal. Chinese politicians are then obligated to compete with one another to achieve the objectives of these campaigns, and they are heavily rewarded if they succeed, while potentially being punished if they fail.7 Officials have to compete to simply stay in their roles, and they need to win or otherwise curry favor with higher-ups to be transferred to somewhere better.

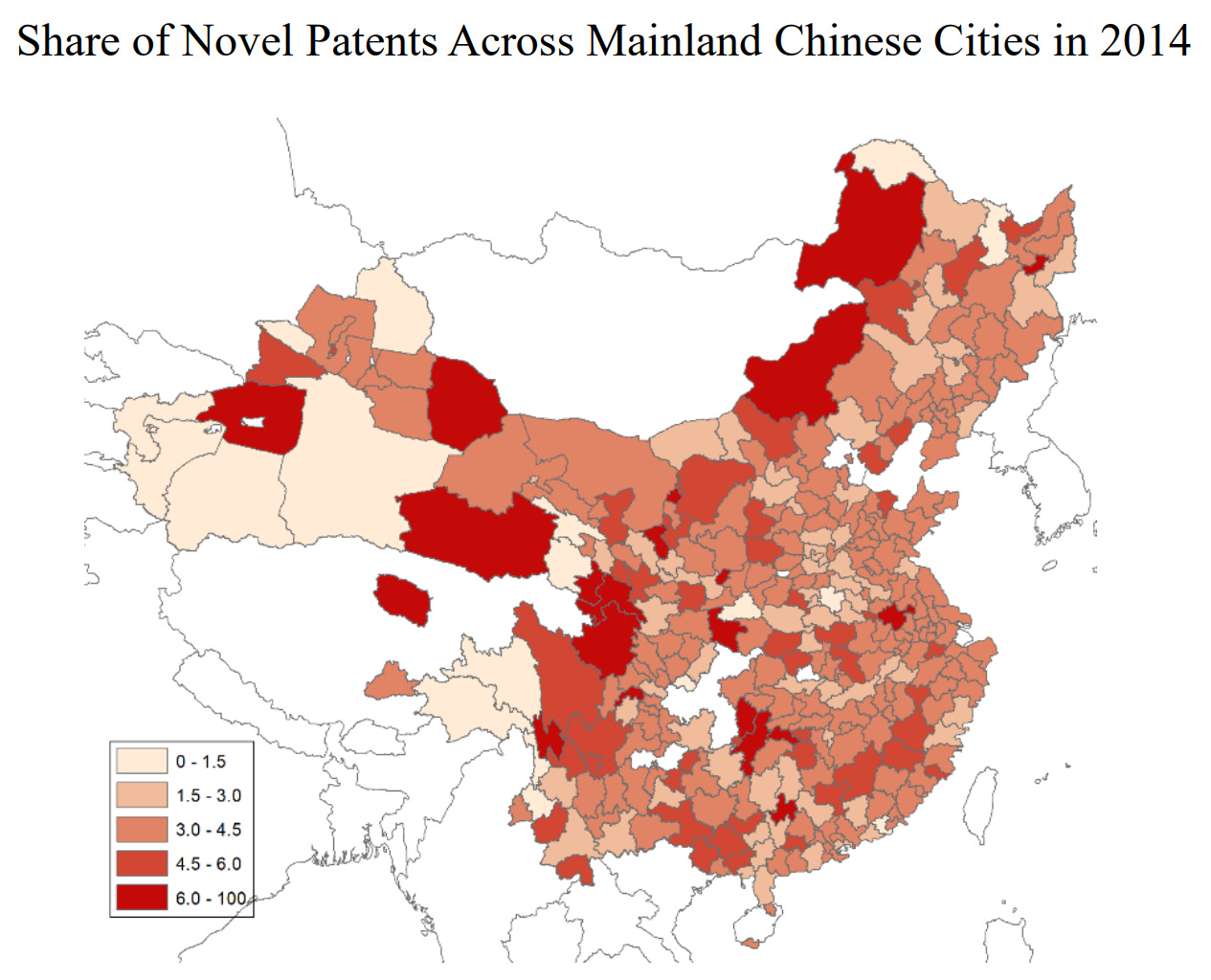

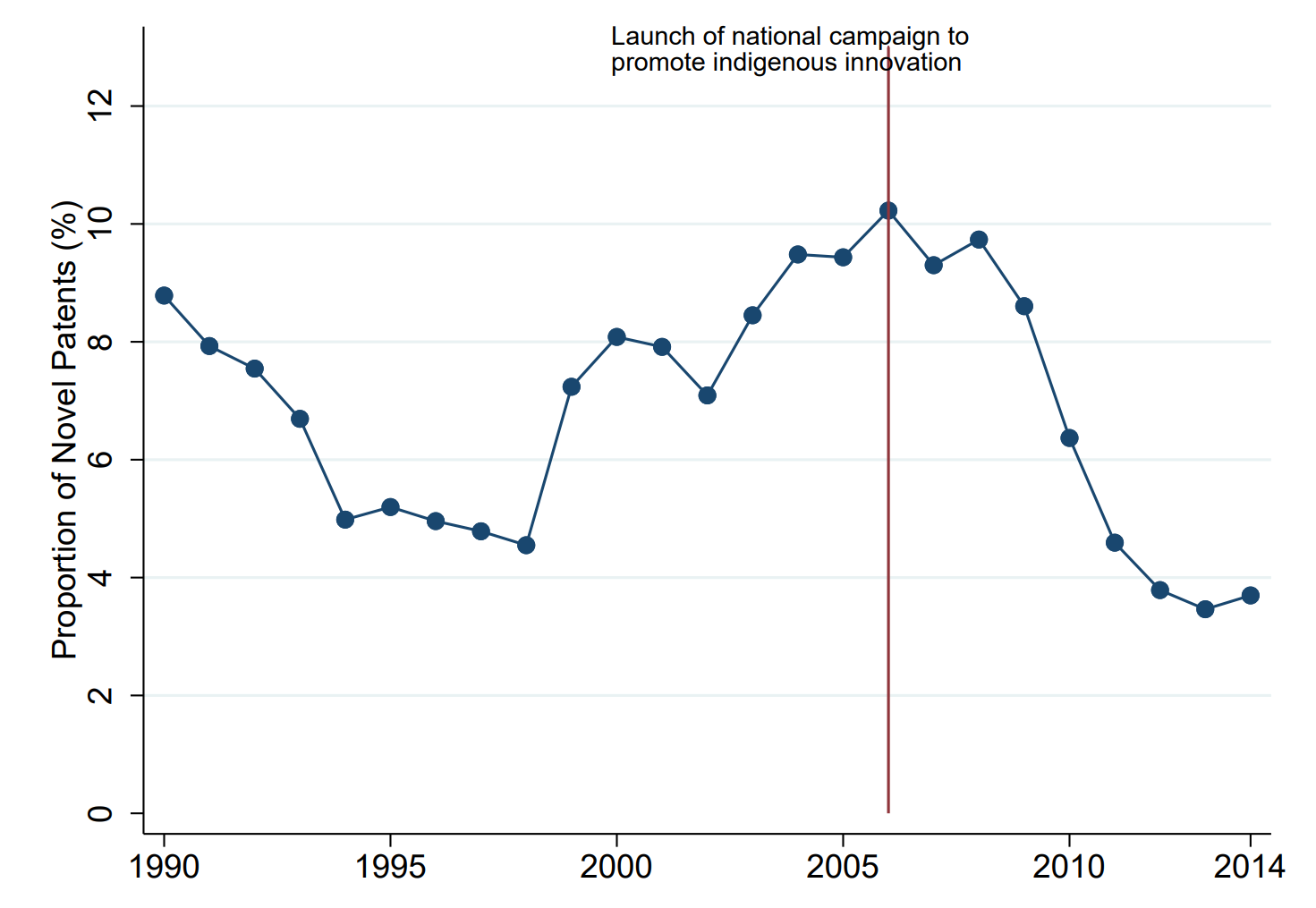

In 2006, China became positively obsessed with innovation because the government wanted desperately for the nation to become the global leader in innovating. The effect of this initiative on patent numbers is readily visible:

If a politician wished to rapidly advance their career during this time, the most straightforward route would have been to follow the fashion and focus on boosting patent numbers. The areas that produced the most patents were, of course, the population centers in the east.

Since those population centers are the most desirable places to live, they are also the places where the pressure to compete was greatest. After all, a minister who couldn’t keep up and thus failed to produce sufficient numbers of patents in their area could be replaced by any number of up-and-coming ministers seeking promotion out of the west. Since, realistically, ministers cannot actually promote innovation, they were incentivized much less to compete legitimately and much more so to cheat. As a result of ministers’ gaming of the system, eastern patents were substantially less creative than ones from the west:

What’s a novel patent? Ang et al. provided examples like “deep sea observation buoy system based on inductive coupling and satellite communication technology”, “visual navigation system of unmanned planes”, “manufacturing of display and polymer-dispersed liquid crystal film”, “wireless communication system, central station, access equipment, and communication method”, and “a robot with flexible structures”. But the majority of patents were non-novel, and these included patents that were practically-speaking, reinventions, or attempts to obtain intellectual property on ideas that already exist or are entirely too simple, like “portable wine bottle cork”, “bicycle cell phone holder”, “adult T-shaped diaper and its manufacturing process”, “processing method of crisp fried sesame sunflower seeds”, and “hot pot soup base and its preparation method”.

Right after China kicked off its campaign to increase indigenous innovation, patent numbers skyrocketed due to the competitive pressures ministers were put under, but the novelty of patents fell in lock-step:

To be sure, patenting did increase the most in areas with the greatest amounts of political competition for positions, but competition also struck a blow against novelty especially hard in those places. Whether this is still good on balance is an empirical question. If you believe it’s good for China to follow a “spray-and-pray” approach to innovation, where it produces innovations in an extremely inefficient manner but at a large volume, then maybe you think this is fine. But, think about it this way: As we’ve seen, China systematically misallocates the people who should be best at innovating into being bureaucrats who compete in ways that make Chinese innovating less efficient. If I had to bet, if China had somewhat less competent bureaucrats and a more competent market instead, it would produce even more and better innovations.

America Wins Because No One Else Competes

Why is America so seemingly singularly capable of dragging the rest of the world into the future? Because no one else is trying. It’s not that America has the best people, or the best education, it’s that America doesn’t siphon off so much of its talent into useless enterprises like China does, or impede so much of its talent from being realized in any way like Europe does. To achieve an even brighter future—and one that’s incidentally less reliant on America continuing to shepherd the way—, the choice is simple: strip away the barriers and bad incentives, and let people build.

December 1, 2025 Update: Fraud and China’s Civil Service

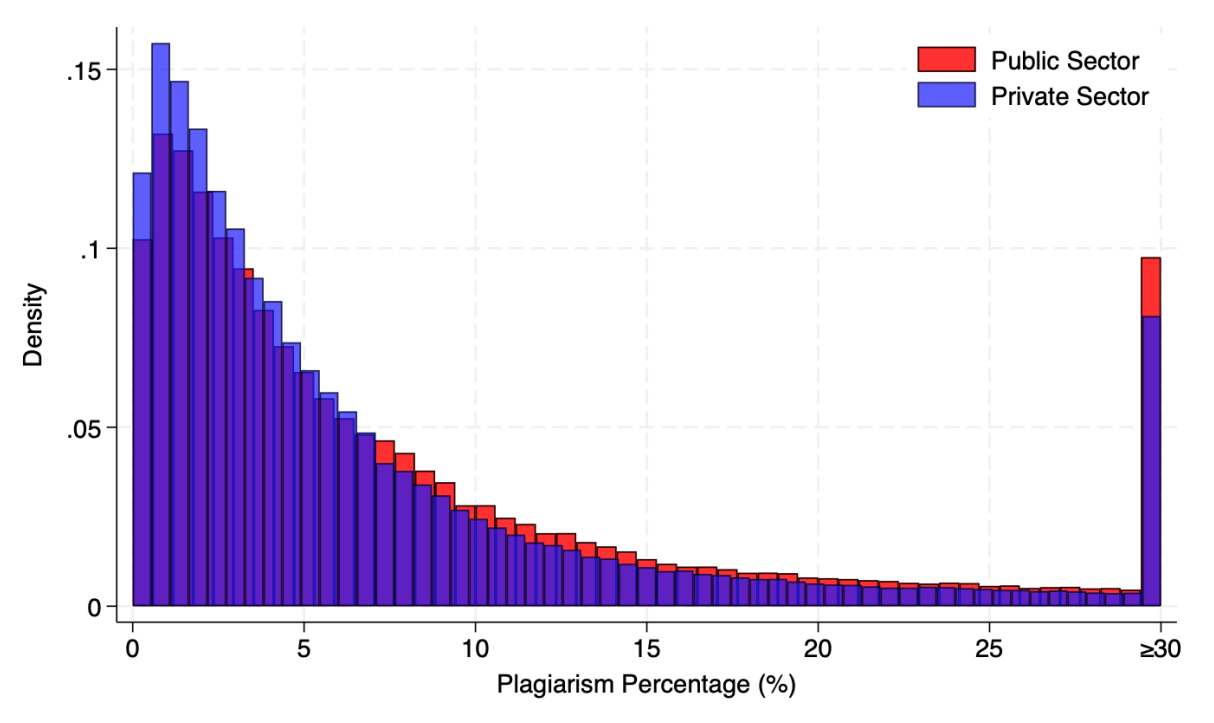

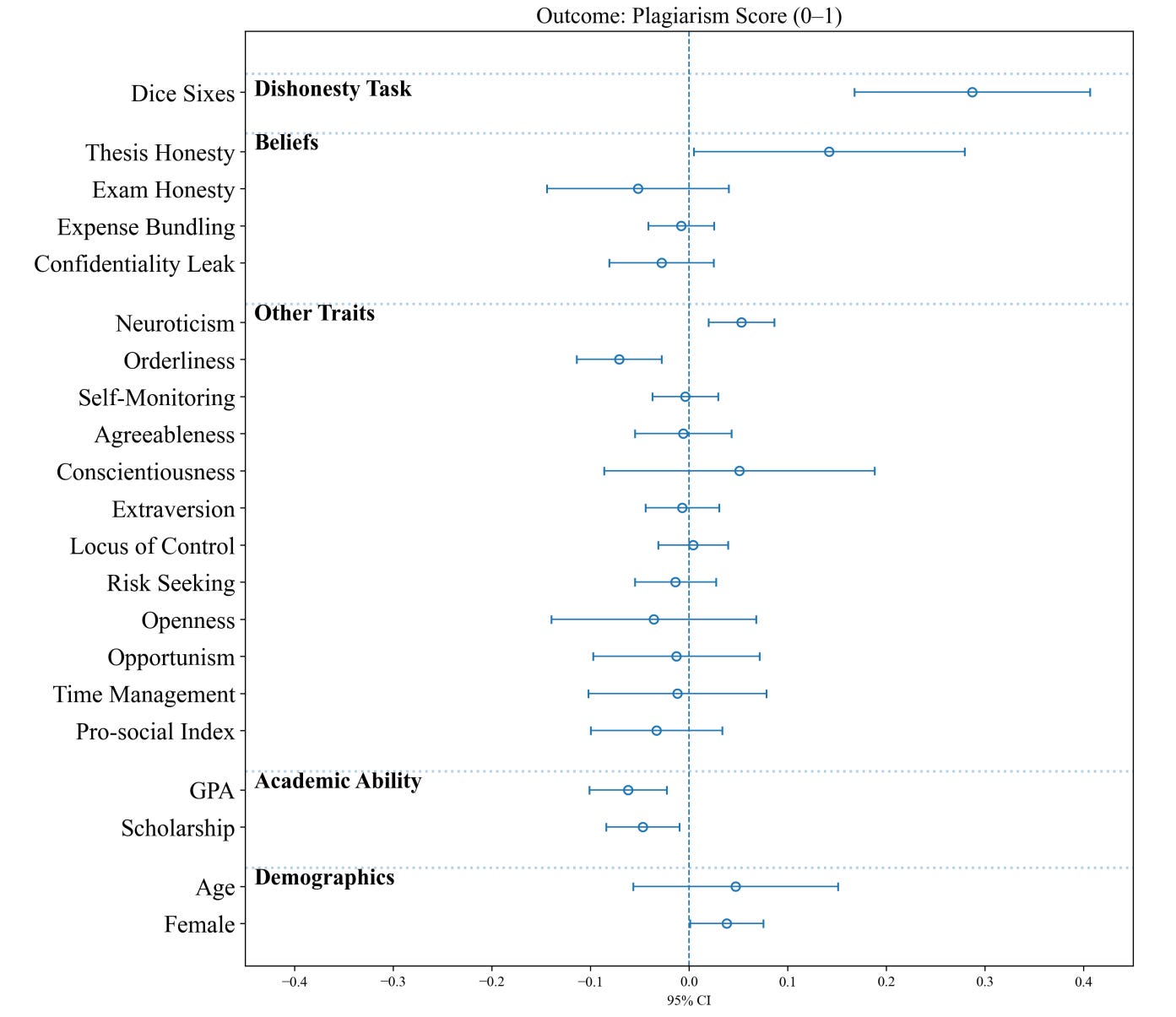

Liu, Peng and Wang found something interesting about China’s civil service. Those who select into it seem to be somewhat more morally compromised compared to those who don’t pursue civil service careers. The evidence comes from plagiarism. People in the Chinese public sector are a bit more likely to have plagiarized on their graduate dissertations compared to people who went into the private sector:

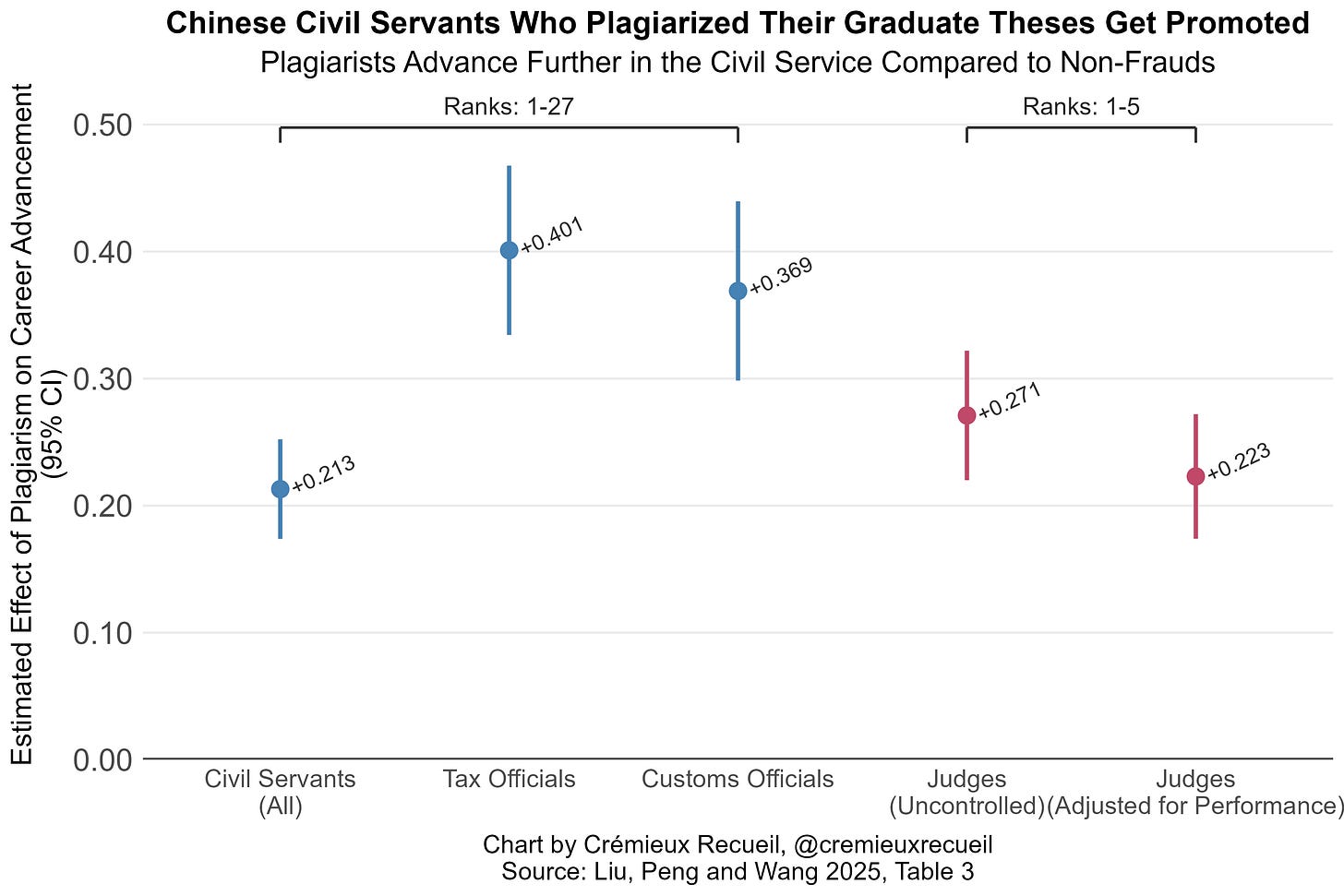

Not only do plagiarists select into the public sector, they also do better in it. In their first few years working with the government, plagiarists’ careers advance further. They earn more promotions, moving up China’s public sector ranks quicker than more scrupulous public servants. Similarly, plagiarist judges move up faster.

Why do plagiarists move up faster? I think the answer won’t be surprising, but let’s look at judges to get an idea.

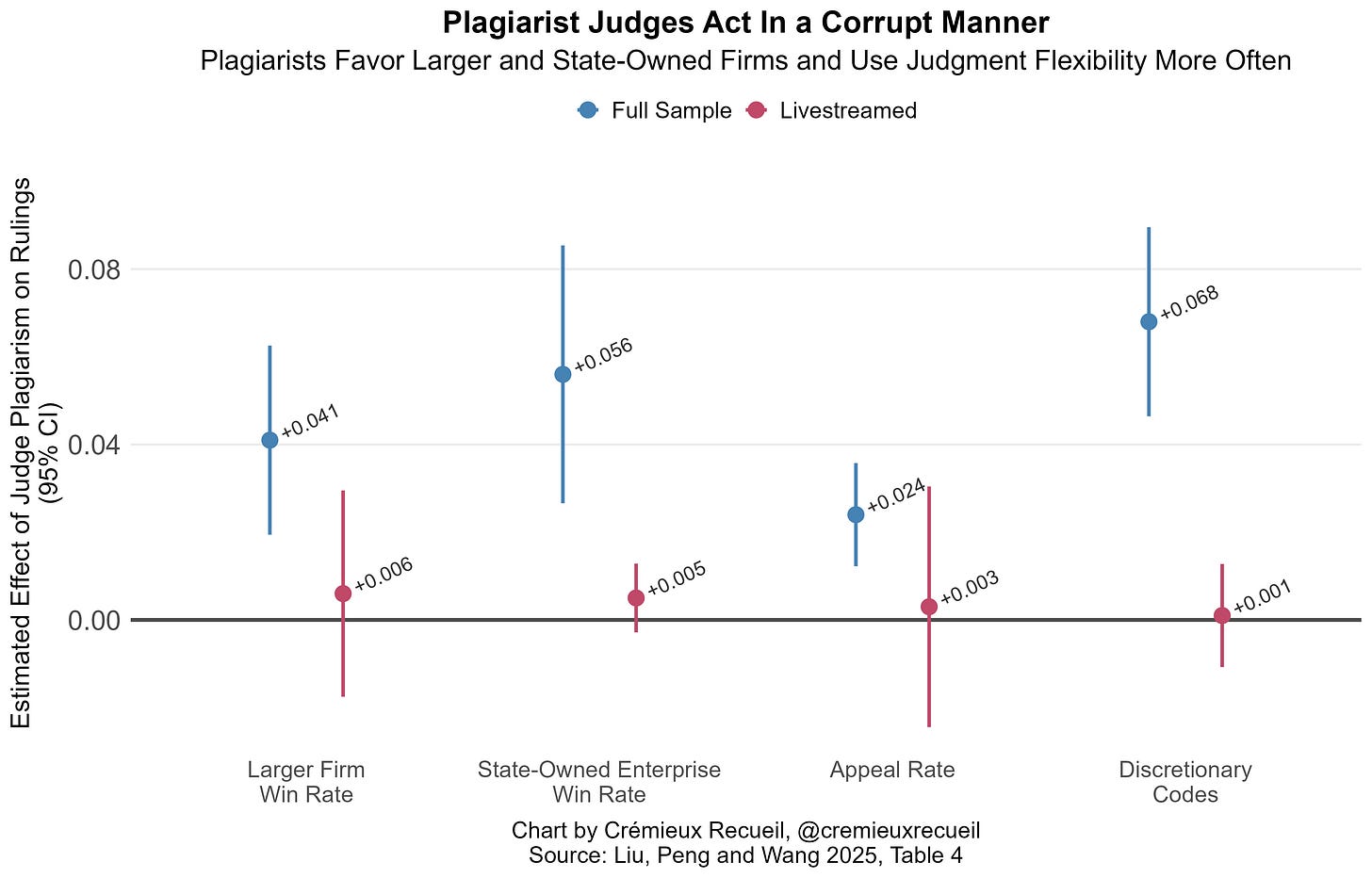

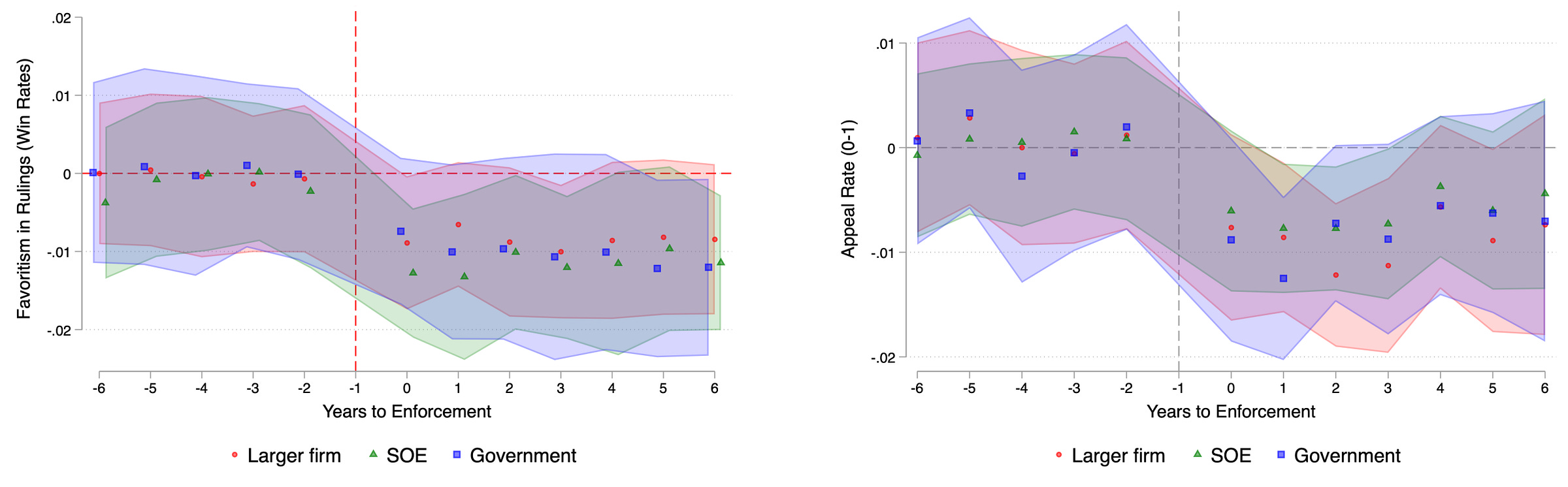

China’s plagiarist judges provide larger companies and state-owned enterprises with higher win rates. They also grant more appeals and exercise more discretion in interpreting and implementing the law. These things only show up conditionally, however. When court proceedings are livestreamed, and thus the judge’s activity can be monitored, the difference between plagiarists and their non- (or at least hopefully less-)fraudulent counterparts becomes practically and statistically nonsignificant.

So, what is the story on why plagiarist judges advance further? They appeal to the right people. They play the game, and it’s clear they know how to play it, because in their cases, they also favor the government generally, and they put in less effort—producing shorter judicial reasoning—when they’re not being monitored. They know why they’re in their position, and they know where they want to go and how to get there. That they’re plagiarists is just part of the game; they knew it would help them advance, much like their other corrupt actions will.

What makes corrupt judges even worse is that there are spillovers. Judges who are mentored by plagiarist judges are also more likely to favor large firms and state-owned enterprises, as well as the government more generally. This effect holds up even accounting for junior judges’ own histories of plagiarism. And somehow, it also spills over to plagiarist lawyers! When a plagiarist judge and a plagiarist lawyer enter the court room together, they’re more likely to provide wins for the clients of the plagiarist lawyer: more contract and non-contract dispute wins, and more administrative wins, too. The corrupt are helping each other out throughout China’s legal system, either by colluding or by playing off one another somehow.

But, you might ask, how valid is plagiarism detection? AI detection is famously bad, and plagiarism detection could easily take properly attributed quotes and call them plagiarized. So, was it acceptable as a proxy for moral corruption? I think so. The authors showed this in a few ways. The first of these ways was that they asked people about their dice rolls in an incentivized dice rolling game (a sort of dishonesty-measuring task), and plagiarists were more likely to report more favorable—and thus less likely—rolls. Moreover, plagiarists were lower-performing academically, as you’d expect given that it’s not only a corruption indicator, but the sort of thing a bad student would be more likely to turn to given that they might need it.

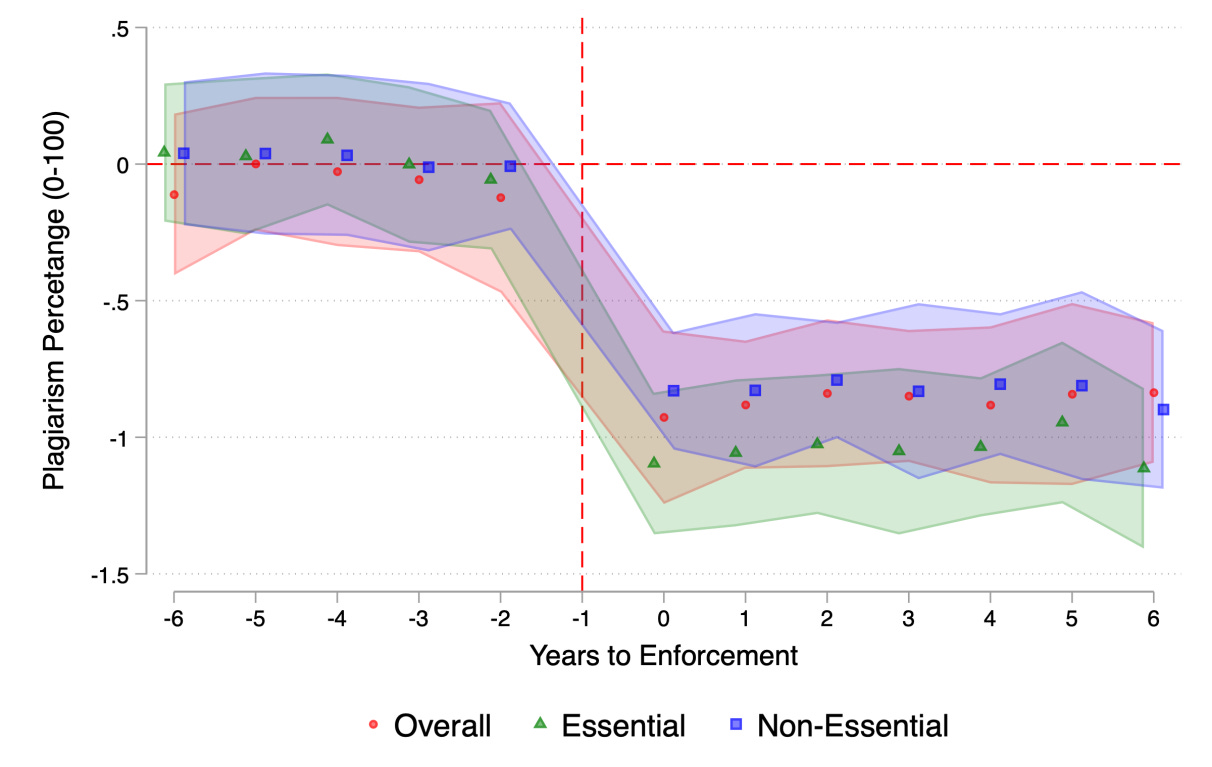

The second piece of evidence comes in the form of an event-study. It just so happens that China recognizes the plagiarism problem, and they’ve sought to crush it. When they implement anti-plagiarism rules, the amount of plagiarism does drop!

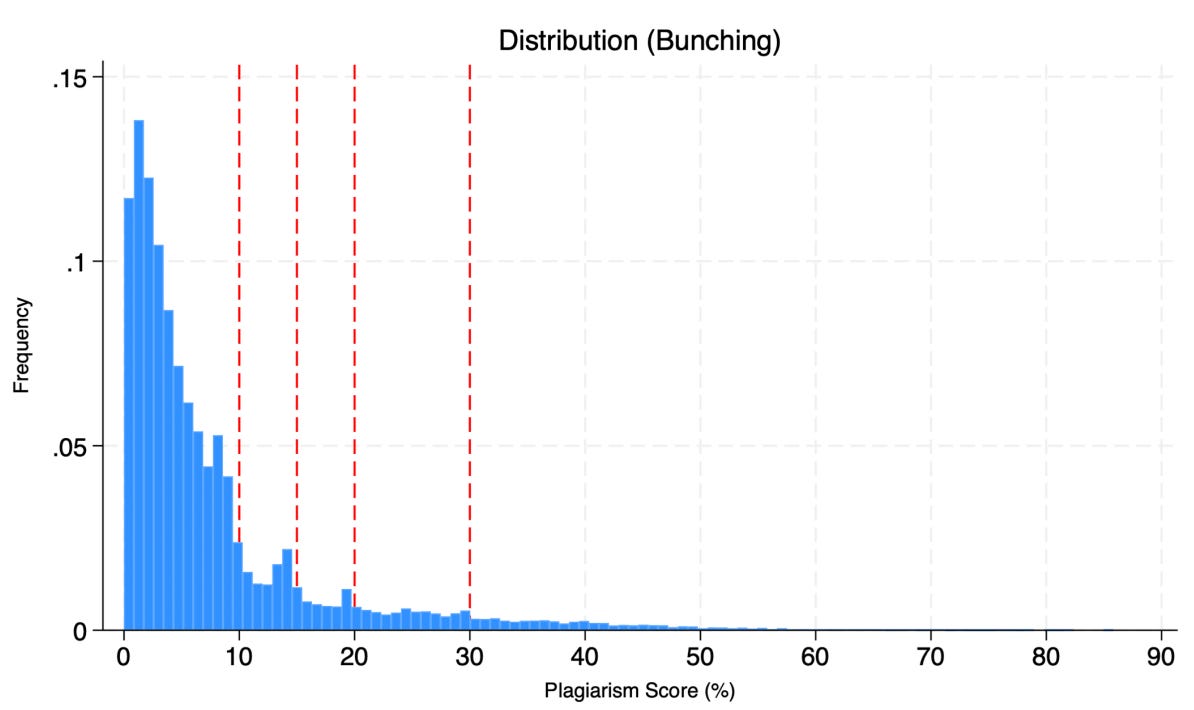

A further piece of evidence that these initiatives work comes from bunching. Sometimes the rules allow people to plagiarize up to a certain amount, and it seems student plagiarism percentages bunch just beneath those bounds:

Whether by selection or training, these anti-plagiarism rules also seem to improve the quality of judges down the line, reducing their favoritism towards powerful litigants (left) and compelling them to allow fewer appeals (right).

In short, plagiarists really are a problem for China, and they are a problem that the government can do something about. But this is perhaps beside the point, which is that China’s competition to get into the government is incentivizing and attracting frauds. Selection into China’s government is not only bad because it draws human capital away from the private sector (where it will tend to have higher returns), but also because it makes the public sector—where moral comportment arguably matters more!—less moral.

These numbers seem high if you don’t remember that lots of businesses fail every year too.

As noted in this study:

Herrnstein and Murray estimate[d] that 70-80% of the Americans occupying [CEO] positions have an IQ of 120, i.e. belong to the top 18% of the population in cognitive ability. The median Swedish large-firm CEO belongs to the top 17% of the population in cognitive ability.

And:

Wai estimates that 38.6% of the CEOs of Fortune 500 firms attended a school requiring standardized test scores “that likely place them in the top 1% of ability.” We find that 17% of large-firm CEO belong to the top 4% (not the top 1%, a much tougher screen) in cognitive ability. While Swedish large-firm CEOs are running companies that are on average smaller than the Fortune 500 firms, they are still the largest firms in the country.

And there were correlations between cognitive ability and success in categories like CEOs of non-family firms, among external, founded, and heirs to family firms, etc. For a review on financial success and intelligence, see Eber, Roger and Roger (2023).

To be clear, this is not a dig against having highly capable government officials in general, it is a statement about the impacts of having an enormous, cognitively selective government that pulls the most talented people in each generation out of the market, crowding out innovation and the most productive activities. There is simply not much room for bureaucrats to push the economic growth envelope, but there is for brilliant people who are in the private sector. With the scale of China’s government, those brilliant people end up working there instead of where they could do the most good.

For founding any company, there are 17% more foundings from the top 10 universities than from those ranked 100+. For founding a company with at least two million RMB in registered capital, they have 45% more foundings, and for companies with at least 15 million RMB registered, they have 58% more foundings. The same pattern is observed comparing those in the top 10 to those in universities ranked 11-100, or comparing those in universities ranked 11-100 with those ranked 100+.

The shown results are firm-level, so the results for registered capital and being listed are not significant, but they would be at the individual level.

After making this post, I created a chart showing that, accounting for all misreporting in GDP figures, the benefits to economic freedom in terms of per capita income levels, per capita income growth rates, and the benefits to per capita growth rates when economic freedom increases, are all underestimated. In other words, liberalizing is probably more economically beneficial than it seems to be, as a result of governmental misreporting.

As a caveat, this is how these people believe promotions work, but it might be the case that China’s government is less meritocratic than its members feel it is and observers have suggested it is. But all that is required for bad incentives to have an effect is belief.

This analysis is based on a lot of very shaky assumptions: e.g., (a) That "start ups" are somehow automatically better than other uses of capital; (b) That smart government employees don't add value to the Chinese economy; (c) That wasting electricity is the best measure of true GDP.

Meanwhile, all the empirical data says that China is miles ahead in manufacturing and infrastructure. If anything, I'd be inclined to believe that GDP methodology overstates the U.S. economy by overvaluing financialization, services, and asset bubbles.

"China is funneling its best and brightest into government and that makes them weak."

This is a bad take. China is a developing country that depends heavily on state led investment. That requires highly capable people running the government. Having a smart civil service that can put the interests of the development of its people first is how they lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Compare that to the civil service in Latin America, Middle East, or Africa. Do you think there are enough smart people in government there?

Singapore's civil service is also highly competitive and highly paid. Its ministers are paid millions of dollars comparable to CEOs of private companies. That attracts talents. Now China doesn't pay its ministers millions, but there's a prestige associated being a high rank government official.