The Ottoman Origins of Modernity

Would we have the modern world without Islamic incursion into Southeastern Europe?

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

This is the fifth in a series of timed posts. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. I gave myself two hours for this one. Check out previous examples here, here, here, and here. I placed the advertisement before I started my writing timer.

The Catholic Church has a long history of successfully suppressing heresy.

In the fourth century, the Arian heresy was founded by Arius, a Cyrenaic priest who professed that Jesus was created by God and was therefore not co-eternal with Him. The Council of Nicaea condemned Arianism and the heresy was a focus of suppression for centuries afterwards. In fact, the Nicene Creed seems to be explicitly anti-Arian.

In the fifth century, the Pelagian heresy was founded by Pelagius, a British monk who taught that original sin didn’t taint human nature and that people could achieve salvation through their own efforts, without divine grace. The Council of Carthage condemned Pelagianism and the heresy was suppressed for centuries afterwards. The fifth century also saw the rise of the Nestorian heresy, attributed to the Greek archbishop Nestorius and denounced by the Council of Ephesus and suppressed thereafter for its attempt to separate the divine and human natures of Jesus and claiming that Mary should only be called the bearer of Christ (Christotokos) and not the bearer of God (Theotokos).

Various strains of Monophysitism rose during the 5ᵗʰ through 7ᵗʰ centuries and they were suppressed after their denunciation at the Council of Chalcedon. The Catharist dualists arose beginning in the 12ᵗʰ century and they were suppressed during the Albigensian Crusade and the Inquisition. Likewise, Waldensianism arose in the 12ᵗʰ century and directly attacked Catholic hierarchy and was declared heretical and then persecuted by the Inquisition.1

More successfully, Jan Hus’ followers criticized practices such as the sale of indulgences and called for sweeping reforms to the Catholic Church in the 15ᵗʰ century. Hus’ movement resulted in in his burning at the stake for heresy and the subsequent Hussite Wars, which culminated in the Church making concessions to the moderate Utraquist Hussite faction and the destruction of the radical Picard faction. Ultimately, the Hussites—whose traditions live on in the Moravian Church—achieved something for themselves, but they were still less successful than the movement they were the prototype for: Protestantism.

Protestantism was unlike these other heresies in two important ways: it survived and it prospered. But why? The traditional story is that the invention of the printing press (c. 1440) made it possible for Lutherans to avoid their predecessors’ fates. But I don’t believe that’s the right story. I think it’s no coincidence that the Lutherans survived and prospered when the Ottoman threat to Europe was larger than ever. Were it not for the fact that the Ottomans distracted the Habsburgs and the Church, Protestantism would have been like other Christian heresies: ultimately minor and suppressed. The timeline leaves little room for doubt.

Push and Pull in Southeastern Europe

European rulers and the Church had taken the Balkans for granted as buffer territories between their domains and the Ottomans, but this mindset didn’t last the Sack of Constantinople and the Ottomans’ seemingly unfettered advance north. When the Ottomans were at the borders of the Habsburg domain and rearing for war with the other claimants to Rome, the fighting within Europe over the matter of Protestantism practically came to a halt, and the number and intensity of feuds, skirmishes, and so on between members of the different Christian denominations declined substantially.

I remarked in a previous article that

Ottoman warring against Europe led to peace within Europe. Feuds and conflicts between European states declined in response to Ottoman invasions, and considerable consolidation took place in sites where there was contact with the Ottoman threat.

The author of the paper supporting that contention wrote in his book War, Peace, and Prosperity in the Name of God that

What we see here is consistent with the hypothesis that the Protestant Reformation was aided and abated by the Ottomans’ European aspirations: the number of the Ottomans’ military engagements in Europe, for the most part, did exert a negative dampening impact on the number of Catholic-Protestant feuds. This impact tended to decline over time, although in any given year, an Ottoman military conquest in the Balkans or eastern Europe reduced that number anywhere between roughly 25 and 40 percent.

[… The] Ottomans’ military engagements outside Europe typically had positive and statistically significant effects on intra-European wars and conflicts—that is, the tendency for the intra-European feuds to escalate… rose as the Ottomans got bogged down in domestic uprisings in their own territories in Anatolia, the Middle East, or North Africa or as they undertook campaigns in the east, the north, or the south against other rivals, such as the Persian or Russian Empires.

[… The] intensity of military engagements between the Protestant Reformers and the Counter-Reformation forces, such as the Schmalkaldic Wars, the Thirty Years’ War, and the French Wars of Religion did depend negatively and statistically significantly on the Ottomans’ military activities in Europe.

It is a matter of historical record that these statistical conclusions are correct. Supporting that view, in Stephen Fischer-Galati’s Ottoman Imperialism and German Protestantism: 1521-55, he wrote that, knowing the Sultans Bayezid and Selim spent much of their time fighting in the Middle East, Emperor Maximilian turned to the German Diets to shore up Europe’s eastern defenses while their attentions were turned elsewhere. In Diarmaid MacCulloch’s The Reformation: A History, he wrote:

In the aftermath of Hungary’s fall, the emperor Charles V tried hard to get the rulers of western Europe to finance more traditional crusades. Even as late as 1543, Henry VIII, far away in England, was prepared to sponsor a nationwide campaign to raise money for his brother monarch’s effort (despite their being on opposite sides of the Church’s schism), but the general political will had gone amid the bitterness of the Reformation. Martin Luther went so far as to consider Charles’ effort futile, because he considered that the Turks were agents of God’s anger against sinful Christendom—and no one could resist God. Indeed, the Turkish invasions were, paradoxically, good news for Luther. If Charles V had not been so distracted in his efforts to save Europe’s southeastern frontier, he would perhaps have had the will and the resources to crush the Protestant revolt in its infancy in the 1520s and 1530s. When Charles did strike, it was too late.

Dieting the German Way

The pace and power of the Ottoman advance contributed to an urgent need for the Pope, Charles V, and Ferdinand I to align with the Protestants to repulse further advances. Many of the Holy Roman Empire’s princes had already converted to Protestantism by this point, and so the forces under Protestant command were doubtless invaluable. Their importance to the Pope-Charles-Ferdinand axis was so great and obvious that Luther and his converts saw war with the Ottomans as a means of gaining acceptance for his movement.

Fischer-Galati’s work contains a detailed telling of the negotiation process between the Protestant German Diets and the Catholic Church and Habsburg family. Ferdinand, in his quest to save Hungary from Ottoman conquest, repeatedly sought out German help because there was no other way to reinforce his realm and repulse the invaders. But contra the axis, the Germans initially didn’t care much about the Ottoman issue and preferred to sit about, discussing the religious issue.

After the Turkish capture of Belgrade in 1521, Charles called for the Diets to assist in combatting the Ottomans and they responded not by sending help, but by convening a commission to meet in Vienna to discuss the Ottoman issue and the amount of aid required to deal with it. The attitude they adopted was “wait-and-see” rather than ‘protect Crown and Christendom’ and this only changed in 1526 when it became clear that Hungary was genuinely threatened and its fall would endanger German lands.

At the 1526 Diet of Speyer, the German princes made their demands for toleration of Protestantism explicit and in no uncertain terms tied them to assistance in the fight against the Turks. Per Fischer-Galati:

The estates declined to consider the question of assistance to Hungary before solving the German religious problem…. [Ferdinand] could either accede to the wishes of the estates or dissolve the Diet [without gaining assistance]. Turkish pressure on Hungary was too great for him to choose the latter alternative; therefore, he reluctantly agreed to the former.

The Edict of Worms that had proscribed Luther’s teachings and declared him a heretic was temporarily suspended and assistance for the Habsburgs was secured. But the Habsburgs still wanted to crush Protestantism, they just had to wait. Three years later, Ferdinand repudiated the decision to suspend the Edict of Worms at the 1529 Diet of Speyer, and various electors, free city agents, and princes wrote up the Letter of Protestation from which we get the name “Protestants”. But though these people refused to accede to the demands of the Habsburgs when it came to the matter of giving up their evangelical faith, they nevertheless provided the Habsburgs with men later that year in order to repel the Ottoman invasion of Vienna. Heretics, after all, were preferable to infidels.

After 1529, requests to assist against the Turks were always accompanied by requests for religious concessions.

When the Protestant Schmalkaldic League formed in 1531, Ferdinand initially sought to oppose it, but by 1532, the advance of Suleiman the Magnificent convinced him it was better to wait on opposing them and to, instead, accede to demands for toleration they had made at the Diet of Regensburg, securing assistance, or at least, holding off additional trouble in the realm.

Less than a year after the Protestants started the Schmalkaldic War—which they failed to commit to in a unified and decisive way—they lost and Charles V reaffirmed the Catholic faith of the Holy Roman Empire with the proclamation of the Augsburg Interim. But, a short few years later, Charles’ ally in the Schmalkaldic War, Maurice, led a revolt in favor of toleration for Protestantism. The Protestants won this Second Schmalkaldic War, earning them the Peace of Passau, and later, an end to the religious civil warring in the form of the Peace of Augsburg, which let rulers choose Catholicism or Lutheranism as their faiths.

The Peace of Augsburg didn’t last, however, and the reason is linked to the Ottoman failure in the Battle of Lepanto.

After the Christian victory at Lepanto, Ottoman pressure on Europe was substantially reduced, and their ability to advance by sea was cut off. As a result of this setback for the Ottomans, peace arrived in Europe for a time, leading to the horrifically violent religious conflict of the Thirty Years’ War. As recorded in the Augsburg Historical Atlas of Christianity in the Middle Ages and Reformation, the devastation of the war left absolutely no choice but to pursue religious peace:

It became apparent after the Battle of Nördlingen that the Catholics could not hold northern Germany, nor the Protestants, southern. This ought to have ended the war, but it rumbled on for thirteen terrible years, until, after lengthy negotiations, a spirit of compromise prevailed and finally, in October of 1648, the Peace of Westphalia was signed.

Though this was a war of religion, it failed to change the religious picture in Europe, and the Peace of Westphalia’s reaffirmation of the Peace of Augsburg with the added acceptance of Reformed Churches created a religious situation that would remain substantially unaltered from the situation in 1624, with the exception of the Counter-Reformation gains made in the land holdings of the Austrian Habsburgs. With the Peace of Westphalia, the Catholic Church and the Habsburg family had finally come to accept a religiously pluralistic Europe.2

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

The Perils of Popery and Promises of Protestantism

In my view, the advent of Protestantism in Europe was a watershed moment for the continent and the Ottomans made that moment possible. The claim that the Ottomans are responsible for modernity is tongue-in-cheek. No one seriously contends that the Ottomans were directly responsible for the innovations that made economic growth possible, nor for the institutional developments that made it it possible to innovate. But many people believe that Protestantism was, if not responsible, extremely important for those developments.

The momentous character of the Protestant Reformation is hard to doubt. Scholars have noted the boons that came from3 Protestants’ promotion of mass literacy4, they’ve suggested that Protestant refugees enriched the lands they traveled to and that Protestantism is a fairly democratic faith, and its corresponding promotion of communal, locally participative government might have helped it to promote creative endeavors. Similarly, researchers have noted that Protestant church ordinances and the need to establish state management capabilities aside from the traditional institutions of the Catholic Church led to greater public service provisioning and investments in state capacity which attracted intellectuals to Protestant towns and cities and also promoted growth in Protestant cities with said laws in general. Others have made the even stronger claim that Protestantism allowed for the creation of the institutional fundaments of industrialization, full-stop.

The most important thing that makes Protestantism great for Europe’s development isn’t any of those things per se, it’s that Protestants were less competent governors than the Catholic Church—that’s not a typo, I said incompetence is what made the Protestants so great. The Catholic Church was always a risk for Europe because it had the power to stop intellectual movements in their tracks, to direct infrastructure development to suit needs that might not help with economic growth, and to impose strictures that could restrict creativity if it wished. To be sure, the Church could and historically often did protect knowledge, but the Church had its limits and suppressed it at other times. Because, in the Malthusian era, knowledge was extremely fragile and small elite contractions could disrupt its transmission entirely, an alternative system that was more robust could quickly end up being superior to the Church if the Church decided to be even somewhat conservative.

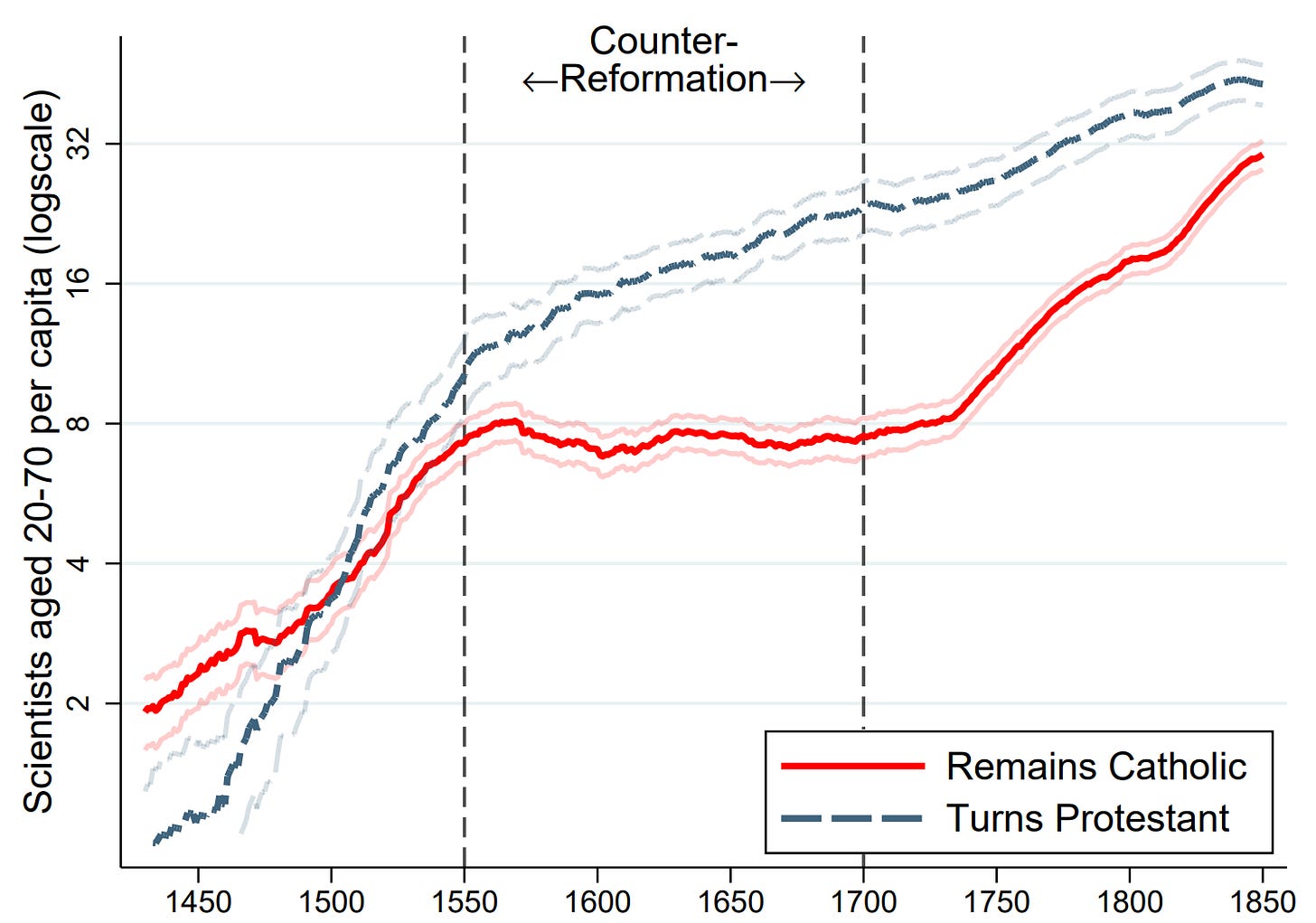

We see the difference in competence play out dramatically in the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Church’s movement to beat back Protestantism and reform itself between 1545 and 1648 (dates vary). This was recently beautifully documented by economic historian Matías Cabello. Take a look at this, a plot of the number of prime-aged (20-70) scientists per capita in European cities that either remained Catholic or became Protestant:

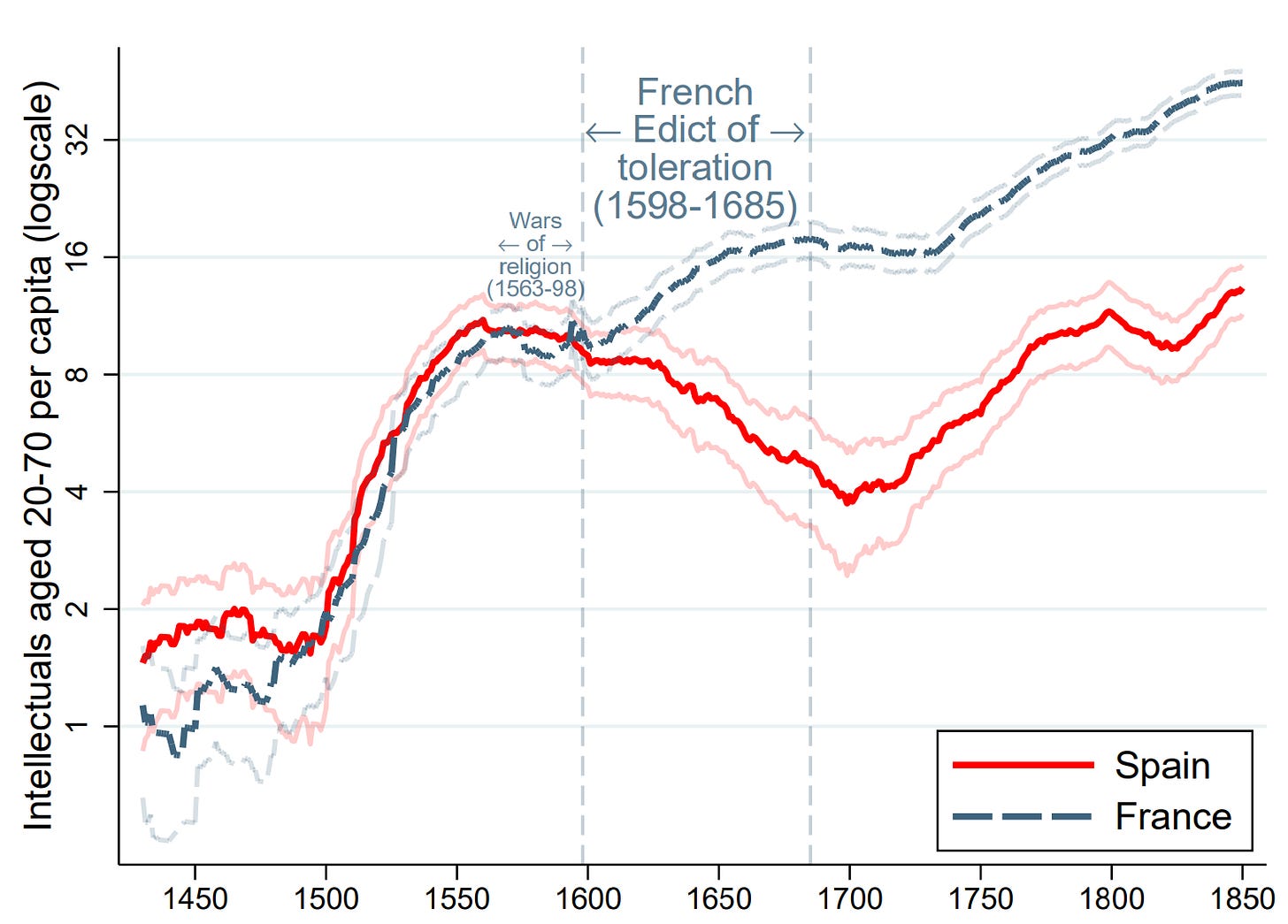

Up until the Counter-Reformation, Europe’s Protestant and Catholic cities were on a similar enough trajectory when it came to the production of scientists, but suddenly growth overall was curbed across the continent, leading to a slowdown for both, with total stagnation in the Catholic cities. If we perform this comparison at the country level, the importance of the Counter-Reformation becomes even more dramatic:5

In addition to losing on scientist numbers, the Counter-Reformation also led to a quality loss, as indexed by the biography visibility of its researchers, who began to lag those in Protestant Europe.6

This shift of human capital to Protestant Europe was not just one of Protestantism creating more human capital or allowing people to express their views more freely—both of which were real parts of the equation here—, but also of individuals with high human capital migrating to Protestant cities and states. More specifically, the right tail of human capital disproportionately migrated to those cities that enacted church ordinances, above and beyond the general positive impacts on city growth. The case of the Low Countries (Benelux) provides a clear case study in the simultaneous effects of all of these dynamics.

The Low Countries were inherited by Charles V and Philip II, both prominent pro-Catholic rulers and leaders in the Counter-Reformation. By the time the Counter-Reformation had begun, the region already contained sizable numbers of Protestants, and they were wealthy and capable enough to stage a revolt after the Spanish had begun persecuting them in earnest. Because of an accident of geography, the north was much more defensible and in that region, the rebels managed to hold their gains and promote their religion, whereas in the south, the Spanish managed to completely quash Protestantism.

As the maps above clearly show, the military logistics of the time cleanly determined a redistribution of scientific progress within the region from Antwerp to further north. Cabello reinforced this conclusion by showing that neither wartime destruction nor plague outbreaks impacted this determination.

Just as well, two other datapoints strongly confirmed that it was Catholic governance rather than Catholic religion that imparted the anti-scientific character of the Catholic world. Firstly, achievement in painting remained undifferentiated between north and south. Secondly, the cities of Breda, 's-Hertogenbosch, Nijmegen, and Maastricht came into rebel hands, but they had been in Spanish hands long enough to undergo the Tridentine Reforms and so they saw no need to convert to Protestantism and the rebels saw no need to foist conversion on them, so long as they remained loyal. Because they were not under the rule of the Habsburgs or directly governed by other Catholic Church-supporting factions that would have imposed literature bans, university control, intellectual isolation and conservatism, inquisitorial activity, and so on, they didn’t scientifically decline.7

The suppression of knowledge by the Catholic Church was so insidious during the Counter-Reformation that, unlike in Protestant and Orthodox Europe within which universities were positively associated with the number of scientists, in Catholic Europe, universities were negatively associated with scientist births. The Catholics were so extreme they had effectively precluded the development of the agglomeration benefits of universities!

Aiding our quest for causal inference and showing us that Catholic institutions rather than doctrine that drove the decline of science in Catholic Europe, scientist’s births appear to clearly be concentrated along the borders of the Catholic domain, or, as Cabello called it, the “heresy frontier”. This makes sense; it is logical to assert greater intellectual suppression where the risk of contamination is largest. It also makes sense that it is the premiere Catholic states, where the Church is strongest where this happens the most intensely rather than in the other parts of Catholic Europe:

From what we’ve seen so far, it should be clear that the Catholic Church specifically attacked science,8 that it did so through means that were extreme, and that where it was incapable of exerting a governing influence, its doctrine alone failed to cause intellectual decline. This is key to the case that Protestantism is important in Europe, because it is not the arts that were attacked by the Catholics, and it is hard to imagine science ever not being what comes under attack, since it is precisely science and its quality of life-improving and religion-devastating effects that would threaten the faith. Even if Protestantism had not happened, it seems very likely that science promoting prosperity in Europe would have led to a Church reaction because science promotes irreligion both directly and through growth. If Protestantism hadn’t been there to provide a release valve for Church excess and the Church had been able to crush science across the entire continent, then who knows if Europe would have ever modernized!

But we’re not done yet. We know the Catholic Church exerted its pernicious influence at different times in different places, and that it did so for different reasons that suggest even more strongly that it was always a possible threat to European progress. In Germany, the separation between Protestant and Catholic cities occurs shortly after the Edict of Worms and right around the Diet of Speyer I mentioned earlier:

Progress in Spanish scientist production diverges from the Netherlands and Britain right after Spain discovers a multitude of Protestant cells in the country, prompting it to implement isolationist laws:

When the Spanish reasserted themselves in the Low Countries, the divergence in scientific production kicked in immediately:

And perhaps most interestingly of all, France managed to substantially but not wholly save itself from the madness of the Catholic Church by issuing the Edict of Nantes, providing its Protestants with some, but not all of the liberties they could have enjoyed in other parts of Protestant Europe:9

The case of England, like the case of France, provides excellent historical evidence for the rule. When Mary Tudor was proclaimed Queen of England, she embarked on her own Counter-Reformation, murdering and expelling numerous Protestants. But she died within a few years and because of this surprising death without an heir and the subsequent Spanish failure to invade England, Protestantism and its accompanying freedoms were able to reassert themselves. Similarly, had the Habsburgs not defended France during its Wars of Religion in 1588-92, Henry of Navarre would likely have ascended the French throne as a Protestant rather than a converted Catholic monarch. These decisive turns of fate are more numerous than just these examples.

Thus far, I have presented what amount to interesting factoids, but I have still not explained why it was the ineffectiveness of the Protestants that made them so great, I have only hinted at it by way of noting the areas in which Catholics were effective at scientific suppression. Extending that line of thought, note that it was the areas with active Inquisition tribunals where the Catholics were most able to suppress scientific progress. Those areas are the ones with the greatest ability to suppress rather than simply those with the greatest will, and we know this because these areas predated the Protestant Reformation in Spain. We know this for another reason that I’ll come back to shortly.

Like the areas in which there were Inquisitorial tribunals, areas with overwhelming Protestant presence of one variety—just Calvinism, just Lutheranism, etc.—also suppressed science. One can hardly forget that the Protestants were not nonviolent, they were simply more frequently forced to be pluralistic by the fragmentation of their religious movement and by the need to stand unified against the Catholics. When they had their way, they could be just as or even more suppressive than the Catholics. In Leeson and Russ’ Witch Trials, they documented numerous episodes of Protestant-led barbarity in the competition with the Catholic Church. Even as late as 1824, the Protestant Prussians prohibited their subjects from studying in places like Tübingen and Basel because they believed the local authorities lacked rigor in suppressing radical ideas.

In a sense, there’s a puzzle in Protestant rule. Because it was so local and not constrained by multinational authorities like the Catholic Church, it was often far more brutal. At the same time, because of the induced pluralism of the Protestant Reformation, it tended to be less suppressive, and its means of suppression were more often ephemeral and violent rather than prolonged, institutionalized, and damaging in the indirect ways wielded by the Catholic Church and its earthly standard-bearers. As I’ve noted before, we even see this play out as late as the election of the Nazis. Cabello also notes:

Protestants had the will but lacked the power. Luckily so: had Protestants been more homogeneous and organized, had the teachers of Calvin—who “himself deprecated science” (Merton, 1938, p. 417)—not led to an increasing number of dissenting sects “bickering and quarreling amongst themselves” (p. 416), or had the anti-Copernicanism of Luther endured, supported by a strong state analogous to Spain, science may have collapsed not just in Belgium and the Mediterranean but in Europe as a whole. That would have meant no scientific revolution, and hence no industrial one.

The Cabello paper is chock full of other results that make each of these points even clearer. For example, the effect of the Counter-Reformation on scientific productivity and city growth—both of which are fundamental to the agglomeration needed to support constant scientific progress—is shown to be strong and persistent. Not only that, but it’s also shown that the institutions the Counter-Reformation brought about or otherwise utilized for suppression—like the Spanish Inquisition—were later revived long after the Counter-Reformation proper had ended in order to suppress other movements in multiple locations. For example, Spain revived its Inquisitions:

Austria resurrected extreme censorship of books after the French Revolution kicked off:

These and pre-Counter-Reformation Catholic institutions of suppression were even leveraged to combat Bolshevism and Nazism (as noted above), and when dictators were Catholic, they tended to make their rule bad for science when dictatorship in general was not.

This institutional angle to explain the Protestant promotion (i.e., non-destruction) of science is so powerful that it even manages to disqualify many other proposed explanations for why Protestantism might have been good for Europe. For example, we know that literacy is not likely to be explanatory for several reasons, like that the decline of science in Spain long predates the decline of literacy, or that broad educational efforts are known to be disconnected from from the density of researchers:

It is well known that the correlation between education and scientific indicators is very high in the present. However, the degree of correlation in early modernity seems much lower. The difference is emphasized by Mokyr and exploited empirically by Squicciarini and Voigtländer, who [studied] the distinct growth effects of broad education (literacy) and elite education (science) in the context of 19th century France. The Dutch, which had by far the highest levels of literacy during the 18th century, did not exhibit higher densities of researchers than low-literacy countries such as France. A similar example of a science-literacy disconnect [comes from] the experience of the Ashkenazi Jewish population. The “utter absence of [Ashkenazi] Jewish names in the roster of intellectual innovators in the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions”, Mokyr writes, “is particularly striking in view of the enormous investment in human capital that Jews made in the education of their children”. “Only in the nineteenth century,”—he continues—”when Jews became assimilated in a secular culture did their contribution become proportional to the massive amount of human capital they had accumulated.”

The “Second Reformation”, we know, is also not associated with especially high growth despite its known impacts on literacy. Most importantly, however, we can be reasonably certain that growth isn’t really down to the printing press, as Cabello controlled for the existence of printing presses up to 1500 using data from the Incunabula Short Title Catalogue.10 Similarly, Richard Crofts suggested that the printing press wasn’t very relevant because “the number of Catholic publications [between 1525 and 1545] was surprisingly high, nearly matching the total of the reformers” and “If Luther’s works are excluded from the reformers’ total, the Catholics outpublished their opponents.”

If you still think there are holes in Cabello’s case, please, read the paper and you’ll probably see your objections addressed in full.

Pluralism Birthed Tolerance

The tolerance of different races, creeds, lifestyles, and even innovation itself, which defines the modern, developed world was borne out of the needs of Protestant reformers and rulers. By doing what was required to prevail over the Catholics, to keep their faith in a world beset with seemingly insurmountable obstacles, Protestantism gave us the modern world. Through providing Protestantism with that opportunity by distracting the Catholics long enough so Protestants could spread their ideas and prosper, encouraging others to follow a diversity of beliefs, the Ottomans gave us modernity.

Consider these parting words from Cabello:

What “propelled scientific advances toward the end of the seventeenth century,” Eisenstein claims, “began with defeats suffered by the Spanish Habsburgs in the sixteenth-century Dutch war—minor scuffles on a corner of the globe, to be sure, but with world-wide repercussions nonetheless.” “Had the [Spaniards] landed in [England],” McCloskey claims, “it seems likely that Europe would have suffered from the innovative sclerosis that infected at the time the great empires further east.” “Had Spain prevailed [militarily] and Catholic conservatives been able to monopolize education and intellectual discourse,” Mokyr speculates, “there may have been no Enlightenment”—thus no “big difference between Europe and the rest of the world,” no sustained industrialization, no modern economic growth.

There are many other heresies also worth mentioning, from Donatism to Gnosticism to Manichaeism to Adoptionism to Bogomilism to the Free Spirit Movement to Jansenism to Lollardy to Priscillianism to Luciferianism (named for Lucifer of Cagliari) to Quietism, but I’ll leave that to others. There are also some potentially heretical doctrines that cropped up outside of the domain the Church could effectively govern, like Paulicianism and the Tondrakian movement.

It should be noted that there’s also a more minor role for Protestant-Ottoman cooperation. Protestantism not only benefitted from the presence of the Ottomans due to the reprieve their role districting the Church and the Habsburgs, Protestants also allied themselves directly with the Ottomans in order to bolster their positions in a few cases, such as when England accepted them as a trade partner. The Ottomans also tolerated both Protestants and Catholics in their own lands, and they relocated the Huguenots from France to Moldavia and they supported Serbian Orthodox immigrants against the Habsburgs.

With peace between Protestants and Catholics, this came to an end and both then generally aligned against the Ottomans.

I also have not talked about what factors promoted the spread of Protestantism initially in this article, instead preferring to discuss the factors that made its spread possible at all (i.e., Ottomans distracting the Church and the Habsburgs). I have talked about the immense influence of Luther, elsewhere, but I want to mention one more thing: Luther did not write his 95 Theses (1517) due to disagreements stemming from the translation quality of Jerome’s Vulgate. He only learned of its issues after the arrival of Philip Melanchthon at the University of Wittenberg in 1518. I do not know the origin of this mistaken belief.

The result in this paper may be attributable to spatial autocorrelation.

The focus on being able to read the Bible makes Protestants like a society of Jews. The Catholic refusal to authorize alternatives to the Latin Vulgate after the Council of Trent (1545-63) had the opposite effect, leaving Catholics substantially less literate than Protestants in little time at all.

This divergence also holds up using important discoveries and inventions instead of scientist or research numbers. See Figure B8 and the surrounding section.

Note that this does not appear to be driven by biases in biographies, as different sources and methods of computing these results strongly agree with one another. For biases to drive the results, bias would have to all go in the same direction coincidentally, and to predict downstream developments in affected areas. Cabello’s paper also provided a more explicit account of why biographical biases are unlikely to explain these results.

Notably, Liège also showed a more minor decline than the rest of the Catholic Low Country because, though it was a Counter-Reformation state with a Catholic religion, it was an independent bishopric. It was effectively Catholic without the intellectual downsides.

Post-publication note: While it should have been clear what I meant given the preceding paragraphs, what I mean here is rather than intellectuals involved in, say, music and painting, and I am not saying that Catholic suppression of scientists wasn’t an off-target hit on science.

It is also worth noting that France declined somewhat when tolerance was removed and it began progressing again a short time after toleration was reintroduced around 1715.

Additionally, Cabello noted that it was unlikely that the printing press could explain Protestantism’s rise:

In Germany, for example, the adoption of Protestantism cannot be explained by any positive association with printing, universities, and economic indicators; rather, as Cantoni notes, it fits a military-logistics interpretation: adoption happens first far from Habsburg territory (military retaliation being less likely there); and cities close to Habsburg territory preferred to remain Catholic until neighboring Protestant states could offer military protection. What holds in Germany holds in Europe as a whole: the south and much of central Europe, easily accessible to Spain’s mighty military remained under firm Habsburg and Catholic control (revolts did happen in Italy, Iberia, [and] Bohemia but were suppressed) whereas Europe’s north, being out of the military reach of Spain, could effectively oppose Habsburg hegemonic plans, creating an environment in which Protestantism could develop. There, far away from Habsburg military centers, the “fortunes of war” had a chance, since logistical limitations imposed by distance and geography interacted with contingencies of weather, plague outbreaks, the timely arrival of silver from the Americas, or even the decisions by the commanders in charge.

Agreeing instead with my case, Cabello also wrote:

Among such contingencies, an important one was the degree of military pressure at the great Habsburg-Ottoman front. As many students have pointed out, Ottoman incursions into Habsburg territory diverted the Spanish military toward the Ottoman front and forced the Habsburgs to seek religious compromises, allowing Protestantism to develop. By contrast, when the Ottomans retreated (e.g., when defeated in Lepanto… or when busy combating the Persians), the Habsburgs were able to redirect their might against Protestantism.

Would there have been a Counter-Reformation, which finally did in Galileo in 1633, without a Reformation starting in 1517? Italy had had a good run for a long time before its science tapered off in the 17th Century. The Italian Renaissance Catholic Church had been highly sophisticated and elitist, but in response to the Reformation, it became more populist, honest, and dogmatic.

The usual attribution to the Ottomans is that their pressure on and conquest of Constantinople led to Orthodox scholars fleeing, with their texts of Ancient Greek learning, to Italy in the 1400s. The sudden arrival of multiple ancient texts led not just to the recovery of Greek learning, but to Renaissance Italians developing a critical spirit as they tried to figure out which texts were most authentic.

Conversely, the Enlightenment really got into gear after Vienna was rescued from the Ottomans for the last time in 1681.

You wrote this in two hours?