Why Accelerated Learning Might Matter More For Larger Families

Could accelerated learning offset the birth order effect?

This is the fifth in a series of timed posts. The way these have worked so far is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. I set my timer to 90 minutes for this piece. Check out previous examples here, here, here, and here.

A birth order effect on measured IQs is supported by numerous studies. The reason for this effect does not seem to be parental age—which actually counteracts the birth order effect—either via paternal age-related mutational load accumulation or increasing maternal age-related prenatal burdens. We know the effect is likely to be environmental in origin thanks to family fixed effects models, differences in birth order effects in different immigrant groups, birth order effects that show up in fully-adoptive families and are thus purged of biological effects, differences in birth order effects in multipartnered families that are present for mothers but not the less environmentally-exposed fathers, and birth order effects that show up in with the social rather than the biological birth order when the family had a child die young.

I’ve written about this before; go give that a look before you read what I’m about to write below.

Some studies fail to find support for birth order effects. This is predictable, because birth order effects are usually not that large, the studies that fail to find support for them usually aren’t well-powered to support them, and important control variables like parental age are sometimes not considered when they should be. But large, carefully-analyzed data produces consistent enough results, most of the time.

I say “most of the time,” because sometimes you could do an analysis and feel that everything went right, but you still missed something. For example, because the Flynn effect operates both within and between families, if you tested children at different ages, you might spuriously find a birth order effect or its absence that’s actually just or dispersed by the Flynn effect. Another possibility is that you failed to account adequately for age, resulting in the birth order effect being absent or reversed. This is, in fact, a moderator of the birth order effect that has been observed in the real world. In a 2007 meta-analysis, the coefficient for the birth order effect looked to be moderated by the age of the sample, like so:

If you didn’t know any better, you might assume that your sample that contains a wide range of ages is optimal for testing for a birth order effect. But if the effect reverses with age, you might end up with little more than the effect at around age 12—that is, nothing. If you and a colleague looked at individual studies on either side of about 12 years of age, you could come away thinking totally different things about the birth order effect, and you might both be right.

A natural question is to what extent the replication crisis has been due to situations like this, where people are observing something replicable, but it’s not what they hoped for. Get a large sample of 18-year-olds? Replicable, sizable birth order effects! Get a large sample of kids half their age? Replicable, sizable birth order effects in the other direction!

Unfortunately, if you find the former effect and someone else finds the latter and neither of you can see the age-moderated forest for the study-level trees, you’re out of luck. Interest in your birth order hypothesis might dry up and people could come away convinced it isn’t real—not because of any inherent replicability problems, but because you didn’t have theory to explain the results.

It’s unfortunate but edifying that this has really happened. If you ask people ‘in the know,’ they’ll probably tell you that birth order effects aren’t real, or that they’re only observed for some traits; they might tell you that they’re linked to early life disease exposure or you might hear something about resource dilution in larger families. Luckily, we don’t need to ask people for their opinions since there are already numerous theories we can consult. Consider these four for the birth order effect on IQ:1

Let’s scan the table from the right to the left.

The first theory is that the effect just isn’t there: being born earlier or later has no effect on kids’ measured IQs. When you do see what appears to be an effect of birth order, what you’re actually seeing is some sort of methodological artefact, or you’re seeing the effects of selection into having a very large or a very small family.

There’s not much more to this one. The spurious association theory doesn’t really predict anything; it can explain findings and it can predict them in the limited context of being able to specify how selection happens, but it doesn’t lead to additional theory development or critical tests. So if it were true, there would be no obvious reason why we should consistently observe the birth order effect within families, differently across ages, or with any other qualifier that shows up consistently.

So that theory is wrong and we should look at the next one.

The prenatal theory holds that the birth order effect is due to the maternal environment worsening with each successive birth, with maternal age, or both. It can also be about existing kids getting mothers sick,2 something to do with correlated paternal age effects, or, in the case of twins, with having to share a limited resource pool and ending up worse off due to hitting resource limitations. It does not predict effects in non-biological children or a developmental reversal of the effect. Because the womb does become worse with age, it also doesn’t predict smaller sibling gaps with larger birth spacings, it predicts larger ones. Because it doesn’t explain the potentially selection-related effect of being an only child either, this theory is wrong and we should go look at the next one.

Resource dilution theory holds that the more children there are in the family, the worse off kids outcomes will be, not just because of prenatally available resources (nutrients, oxygen, space, etc.), but because of postnatally available resources (parental attention, the highest possible quality of schooling, housing, and food parents could theoretically provide, and so on).3 Since resource dilution effects should grow with age, we should not see a reversed birth order effect in young samples, meaning that—given everything we know—this theory isn’t sufficient to explain the birth order effect.

Finally, confluence theory predicts all of the phenomena described in the table. This theory is the most complex of the listed explanations; that’s advantageous due to the theory’s implied greater explanatory breadth, but it’s a disadvantage in that it makes it harder to provide tests of the theory and it opens it up to attacks that don’t change its core explanatory value. I’ll explain.

The way this theory works is that it posits that children intellectually develop—at least in part—due to the intellectuality of their environments. After they’re born, firstborn children experience an advantage because their environment is maximally adult-centered and thus richer in intellectual stimulation for the child. When another child is born, the intellectual environment becomes less adult-centric and more diluted. This dilution is intellectual and resource-based, like resource dilution theory. In addition to dilution, there’s a teaching effect, whereby firstborn and other older siblings take on teaching roles with younger siblings, reinforcing their own learning because explaining concepts to others can help people learn.

In essence, confluence theory posits that children reared with younger kids are forced through no fault of their own to live in a less intellectually and possibly materially stimulating environment. The parents have to adjust their behavior to suit the lowest common denominator, usually meaning the youngest child. Parents disperse resources in general and to specific children, and the general disbursements of time, effort, material, etc. will be less intellectually rigorous along many dimensions, from the movies and shows parents will watch with their kids, to the books they read them, the excursions they take, and more.

Because the quality of parental effort is brought closer to the level of the least capable child, the reversal with age that the other theories couldn’t predict can now be explained: the younger child gets the most undiluted, age-appropriate effort; they’re the youngest, and the home environment is tailored the most to their needs, since they’re the most acute. As children age, they become more independent and the initial advantages of first- and later-born siblings reassert themselves over the dilution experienced by their younger siblings.

This theory makes sense, but I also have gripes with it. For one, it’s hard to distinguish it from resource dilution without longitudinal data. More importantly, however, it seems to explain too much. Consider the only-child and twin deficits.

The twin deficit might’ve been larger in the past than it is today. This could reflect that families in the past were larger too, and thus confluence augmented a deficit that was there for other reasons. But, as that meta-analysis points out, later studies—which tend to find a smaller deficit—feature additional controls, including, often enough, for a twin pairs’ number of siblings. In large, modern register studies, the impact of being a twin is usually small and sometimes its existence is dubious. It also might start off larger earlier in a twin pairs’ life, but fade with age. In a response to one of those register articles, Ian Deary once remarked:

Despite… issues, Christensen and colleagues’ study is comprehensive and well executed enough to reverse a trend in our thinking—that twins perform less well than singletons.

Is the state of the evidence such that we can now regard the twin deficit as a relic? Has medical care improved in a way that makes delivery or pregnancy easier on the mother and her twins? I think the existence and extent of the twin deficit is unclear, although I generally lean towards thinking there’s some level of twin deficit and recent studies might have overcontrolled to make it disappear or to turn the estimate so noisy that a sizeable effect becomes nonsignificant and gets dismissed.

Regardless, if there is a twin deficit, it seems like it could be better explained by the prenatal theory and augmented by confluence. After all, there are twin deficits in birth weights and heights and those substantially—but seemingly not wholly—fade with age. If there’s no twin deficit, then confluence theory would be better if it walks back its explanation for that non-phenomenon, because if it doesn’t, that means the twin deficit is a failed prediction and the theory is in some way wrong.

The only-child deficit is a similar phenomenon, in that it could be predicted by a version of confluence theory, but it might not be true, so maybe the theory shouldn’t predict it. The confluence theory’s inventors data showing an only-child deficit was published on in 1979, when families were larger, so things could have changed and being an only-child could have become differently selective.

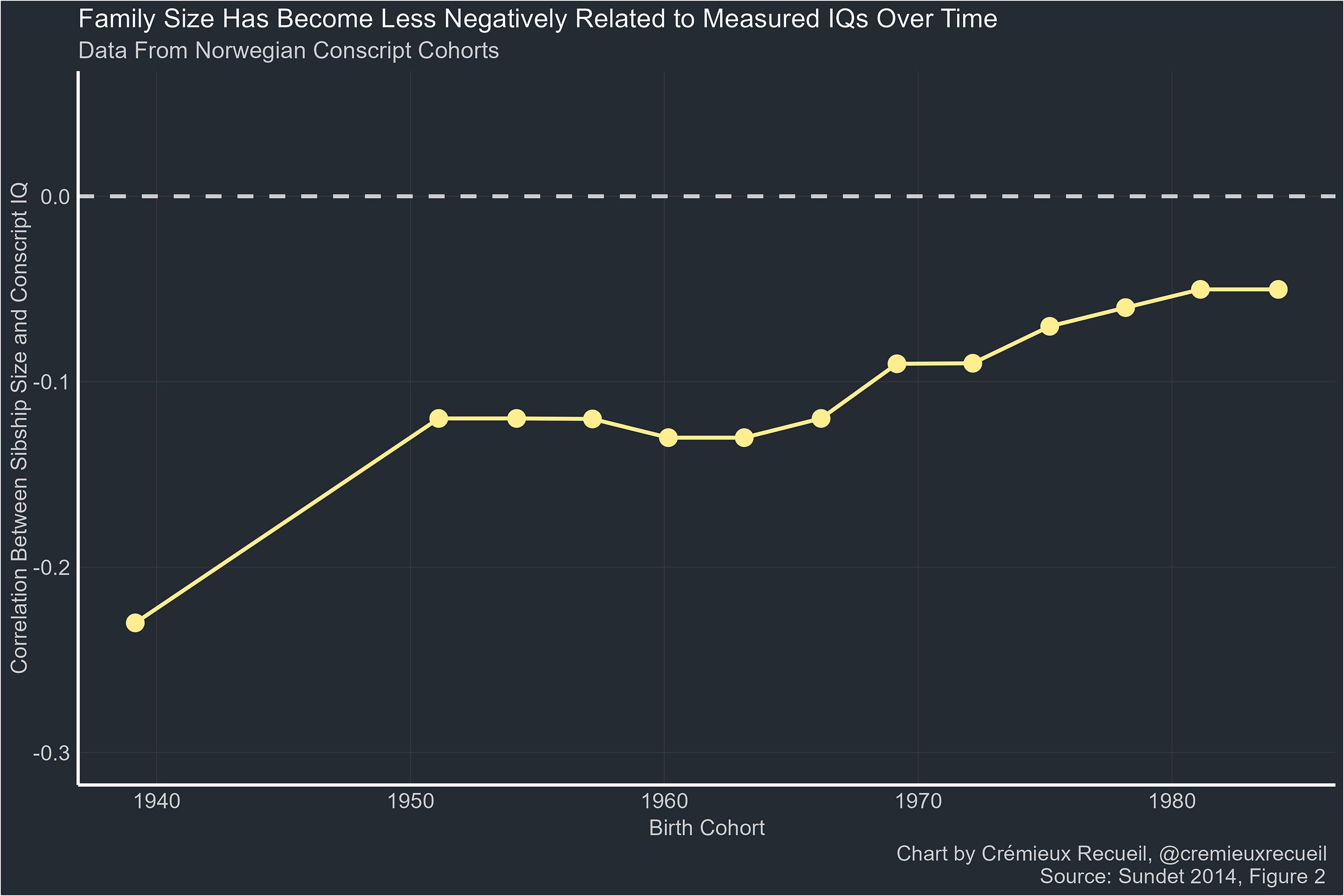

Some more recent studies have found only-children do not show deficits compared to firstborn or later-born children.4 Since family sizes have been falling, recentness could matter; it matters in Norwegian birth cohorts, where the association between having a larger family and having a lower IQ has moved closer to null over time:5

Notably, when families are defined by size consistently, a similar picture shows up:

This could be due to selection—people who would have previously had large families now have smaller ones, something we know has happened to many, but we don’t know for sure is associated with lower IQs6—or economic growth, the welfare state, or a combination of them allowing larger families to provide their kids with relatively better environments, as the smaller families should have seen diminishing returns earlier.

There’s room for selection by family size in many datasets and we should not regard the only-child deficit as a phenomenon we’re certain exists and we’re, thus, certain we have to have theory to explain. At least one study has even suggested firstborn and only-child advantages over later-born children as a prediction of confluence theory, even though the table and one of the graphs I provided above suggest there should be deficits for only-children.

In short, I’m a bit peeved by confluence theory being proposed to explain too much. But I shouldn’t be too surprised that this could be an issue. It is a common problem for theories in psychology in general; when they’re explicated, there’s a problem of explaining far too many things that, ultimately, do not need to be explained, thus forcing theorists to explain why the things their theories were meant to explain are not, in fact, in need of an explanation.7

But no theory is perfect, and this one isn’t profoundly bad. Even if current confluence theory explains too much, it doesn’t seem unlikely that there’s a version that can explain just the right amount. So let’s assume it’s right and reason from it.

Do You Want To Accelerate?

Academic acceleration is associated with many notable advantages for gifted children, and those children tend to see acceleration in a positive light. A different form of acceleration is starting schooling earlier and giving people the ability to set their own pace as they advance through content with services like IXL, Khan Academy, Outschool, Great Minds, Accelerate Education, and Mentava.

If these services do manage to get kids learning earlier and they allow them to speed through school grades-worth of content faster, then there’s a major opportunity here for the rich to get richer if the confluence model is correct.

Let’s say the birth order effect is a loss of 3.5 IQ points for second-born children and, for the sake of argument, that these are real intelligence losses. If the lower intellectual level of the environment, dilution of intellect-stimulating resources, and so on, is at play as a major cause, then to the extent resources like Mentava and Khan Academy can offset those losses, those IQ points can be recovered. If we assume that those resources allow the intellectual level of the family to be boosted even for only-children, then what we’d be suggesting is that there might be acceleration-related gains on the table.

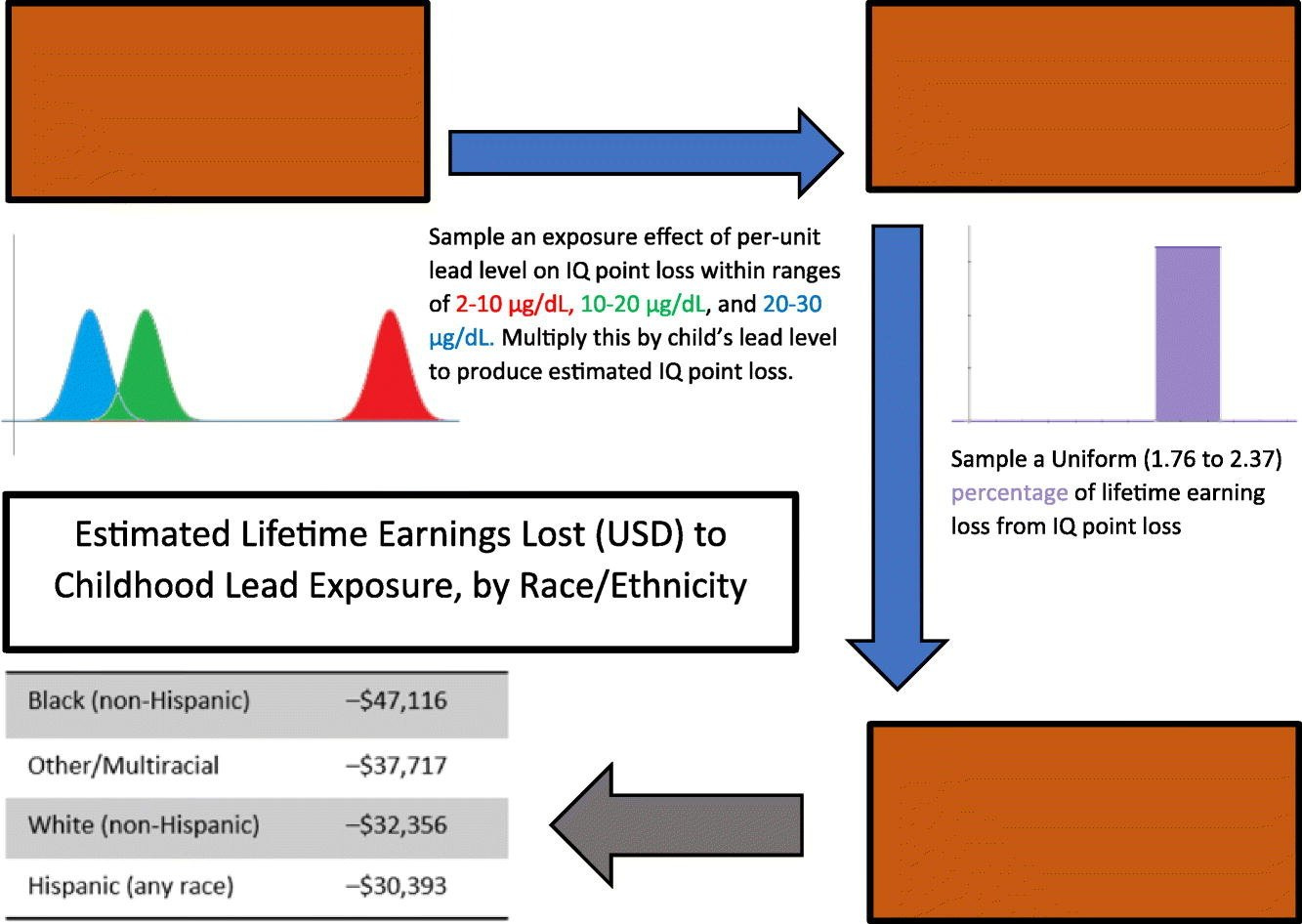

Several people have tried to estimate the lifetime earnings lost due to lead exposure. It’s not clear that lead exposure actually affects IQs (or intelligence), but if we assume it does and that it leads to worse outcomes as a result, then even small impacts can be sizable. Take Boyle et al.’s 2021 estimates, which they’ve graphically summarized:

In their study, they projected that Black kids, Hispanic kids, and White kids, respectively lose out on 1.78, 1.15, and 1.21 IQ points on average due to lead exposure, and that this exposure would thus translate to lifetime losses of $47,116, $30,393, and $32,256, not adjusted for inflation since the study’s timeframe. If early-life learning acceleration results in mitigation of the birth order effect by making it possible for the family environment to be more intellectual than it would have—in other words, reducing the young child penalty on the family—then it could translate to gains of up to (3.5 * 47,116)/1.78 ≈ $92,6448 in earnings over the lifetime. Adjusting for inflation since the study’s publication in 20219, that’s $111,233 as of May 2024.

If acceleration leads to gains—say, of 1.5 points on top of the removed 3.5-point loss—then the value jumps to $132,348 ($158,904 adjusted for inflation). If it leads to a longer amount of time in the workforce because it allows people to get out of formal education earlier, then tack on more, even larger gains because that means more years receiving a salary, more desirability from employers due to younger age, an earlier start to one’s wage growth trajectory, the potential for more10 educational credentials being earned in a shorter or the same amount of time, and so on. With that benefit, $132,348 is almost-certainly an underestimate, and that variety of benefit is possible even if early learning acceleration doesn’t causally increase earnings through boosting intelligence.

These benefits also scale with family size. Third-born children are worse off than second-born children, and fourth-born children are even worse off than the third-born ones, and so on. The more products like Mentava’s can militate against the effects of birth order, the more it behooves parents to use them; the larger their family, the more it behooves parents to use them; the more they care about their kids being able to help provide for them in old age, the more it behooves them.

Giving kids more time to live life as adults and better adult lives is a no-brainer, and it’s socially beneficial too. The more the birth order and family size effects are reduced by truly nullifying the effects—meaning raising people’s levels—the better society will be. That’s one less reason parents could supply for not having kids, and if even a million kids gain just one point of IQ, the social value almost necessarily exceeds the dollar value of their expected increase in earnings—itself already a massive $26,469,662,921 (more than $49 billion adjusted for inflation).

If we’ve been wrong about confluence theory and kids’ IQs don’t rise as a result of acceleration, it’s no matter, since acceleration is still otherwise beneficial.11 So, in short, accelerate: make small families a bit better and large families much better in the process, improve individual lives by making parents proud and kids better off, and make the whole world better as a result.12

Do note:

No studies have assessed whether birth order effects on IQ are “real”, meaning effects on general intelligence—g—or effects on any other important and well-defined latent ability or network of skills, or, for that matter, whether the effects are measurement invariant. The proposition outlined in this article with respect to IQs needs to be caveated with this in mind, and especially so since I personally doubt that birth order affects intelligence. I have written about this before.

Regardless of whether intelligence is actually affected, effects on IQ scores can still have facultative utility, meaning that they matter because higher test scores are valued in their own right, like scores on the SAT, ACT, or GRE. For that reason, if birth order effects are at least sufficiently broad—and they do seem to be—, I still think they could have value regardless of their affinity for intelligence itself.

There’s reason to doubt this theory.

Because parent time and energy that can be provided to each child is a finite resource that can’t be made more available by throwing more money at kids, parents can’t work their way around this theory’s implications on some level.

If we value early-life education to a high enough degree and we do think it’s something that follows parental income, then shocks that lead to higher or lower incomes for kids in the family at different ages ought to have sizable effects. But they do not. That’s not technically disqualifying in its own right since parents who experience a shock might not reallocate resources like people allocate them cross-sectionally, but it is something to think about.

Relatedly, the 1979 paper by Zajonc, Markus and Markus features the now apparently incorrect line “the relationship between intellectual performance and family size is stable and consistently replicable.”

Given the positive association between measured IQs and fertility among neighboring Sweden’s males, maybe this does hold.

When this happens, it should be more damning than it usually is, but people tend to cast aside the problem of overly explanatory theories being self-indicting.

$92,500 with Hispanic and $93,302 with White numbers. I used the one that was in-between either estimate.

Which is later than the study’s dollar values, thus leading to underestimated acceleration benefits.

And better, because of a youth advantage in admissions, higher standardized test scores, and so on.

And it can help limit costs! For example, if you are intent on private schooling or homeschooling all your children, accelerating their educations means fewer years of that, and less total costs, since the acceleration solutions are generally not very expensive relative to paying for complete schooling.

Though not directly related, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention some other interesting and tangentially-relevant studies.

Firstly, there are several studies suggesting confluence cannot be the whole story for birth order effects in general. It could still be part of it, but there’s no way that it explains height birth order effects, nor does it explain so many other health effects; but as I’ve noted before, the IQ birth order effect can be largely recovered from social birth order. In that last citation, there is even a direct analogy to the confluence model, but for health rather than IQs:

Family fixed effects models show a positive and robust effect of birth order on health at birth; firstborn children are less healthy at birth. During earlier pregnancies, women are more likely to smoke, receive more prenatal care, and are more likely to suffer a medical pregnancy complication, suggesting worse maternal health. We further show that the health disadvantage of firstborns persists in the first years of life, disappears by age seven, and becomes a health advantage in adolescence.

The early worse performance of firstborns that turns into an advantage is supported through this more nearly biological realization. On the biology note, there is also a birth order effect on mortality such that the later-born children have higher adult mortality risk.

The birth order effects on health have been supported in other studies, with certain phenotypes reversing the order in ways that, at a glance, seem consistent with social causation and parents learning as they age and gain experience as parents, in many cases.

Cousin birth order effects are also something to consider in addition to traditional sibling birth order effects. These effects show up in sibling fixed effect models, on GPAs, and they are significantly larger if they’re based on maternal cousins. This asymmetry in the effects of paternal and maternal cousins seems consistent with the idea that paternity is more certain with daughters than with sons, and thus extended families should invest more in their grandchildren with daughters than those through their sons.

Finally, I think Altmejd et al.’s paper on sibling spillovers on college attendance and major choice across Chile, Croatia, Sweden, and the U.S. was an exciting read. In short, if an older sibling attends university, younger ones become more likely to attend that college. This effect disappears if the older sibling drops out. Younger siblings follow older siblings not just to the same colleges, but also to the same college-major combinations.

As a parent of multiple children, I enjoy thinking about these issues.

With respect to the learning environment, I think there are trade offs for every kid. The older kid gets the benefit of a few years of mom to himself (if lucky), but they don’t get the benefit of older siblings and stay innocent longer.

My wife noticed on Facebook that parents of seriously ill or disabled kids tend to stop having children. I wonder if this type of selection is a major effect. For example, what if parents of “better” kids are more likely to have more kids, at which point they experience regression to the mean?

Conversely, if parents get a dud kid, they would be more likely to stop out of frustration, and also focus on helping that kid.

With respect to an only child effect, I would assume that such parents are more indifferent to their kids or simply less effective, leading to a worse parenting experience and them being more likely to stop.

You could think of a lot of different selection effects based on the different types of parents. For example, I assume most parents of larger families have to accept that their educational efforts are going to be diluted. I assume the super strivers stop sooner so they can concentrate their resources.