Workers For Robots

Want to give blue collar workers the sorts of jobs they can raise a family on and revive American manufacturing? Then you should support automation

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

This is the seventh in a series of timed posts. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. Check out previous examples here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. I placed the advertisement before I started my writing timer.

The most major source of opposition to automation comes from groups that don’t want people to lose their jobs. This is an easily understood position that hasn’t borne much fruit historically: despite massive levels of automation compared to all of history leading up to right about now, we have more jobs than ever and there’s still ample demand for more labor.

But there are still those who think we’re currently facing an automation-induced employment crisis. Maybe I have myopia, or maybe the near future might be different! We’re entering the era of artificial intelligence and, who knows, AI might be able to finally take labor out of the hands of humans. If it can, then the transition towards all human labor being automated away might have devastating distributional impacts, creating massive gulfs in status between the automating haves and the automated-away have-nots. But in the interim between now and a seemingly-inevitable future where automation proves capable of leaving us all lazy, what should we think about it? Have we reached the point where automation actually is taking away the prospect of meaningful work for the masses, hobbling our collective prosperity, and promoting unprecedented inequality?

Famed economist and recent Nobel Laureate Daron Acemoglu has argued just that in his book Power and Progress:

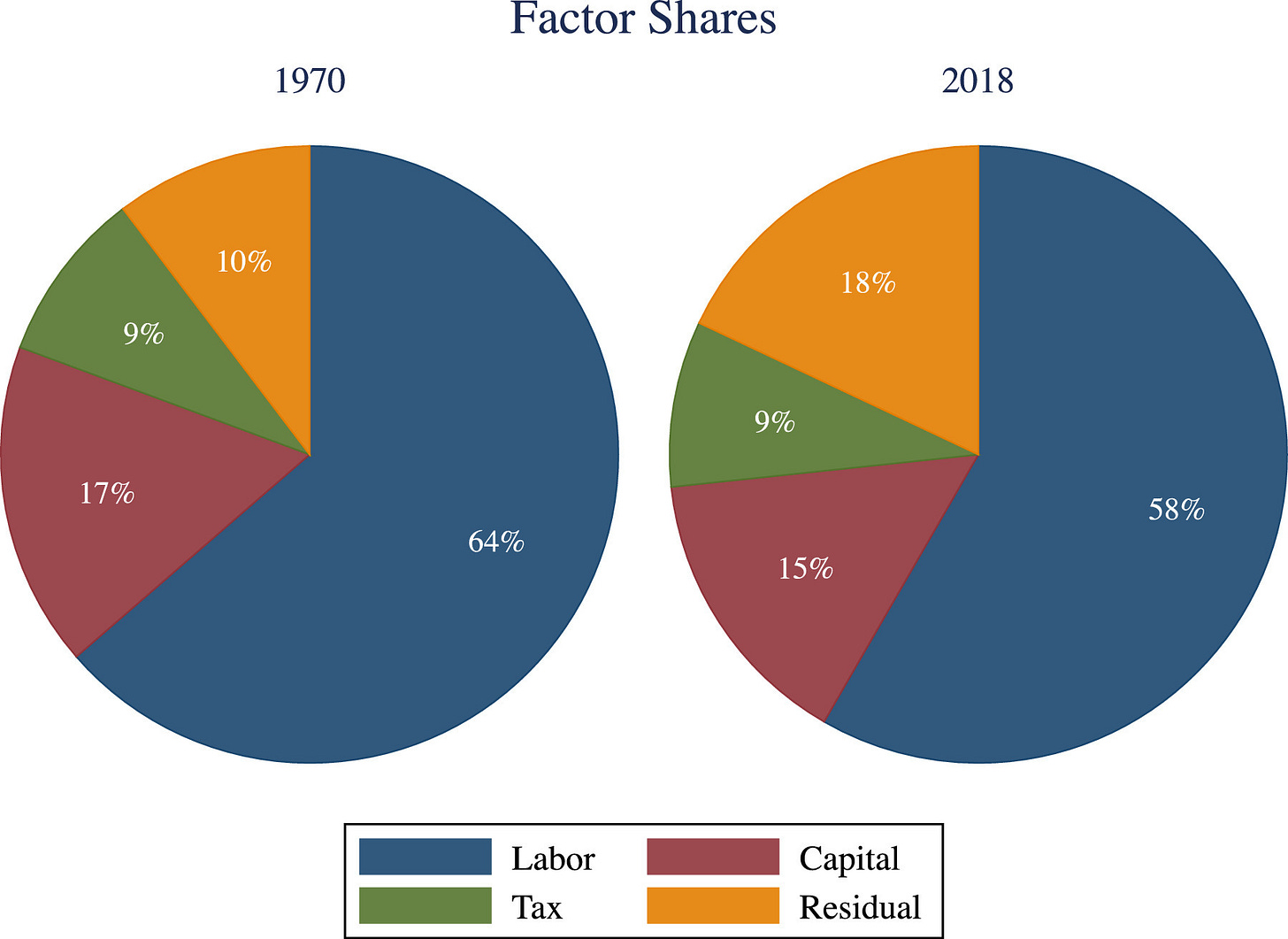

There is a telltale sign of automation technologies: reducing the labor share of value added, meaning that once these technologies are introduced, how much of value added goes to capital increases and how much gets captured by labor decreases…. On this basis, technologies that increase the labor share can be encouraged via subsidies for their use and their development.

The funny thing about this paragraph is that it’s wrong.

Acemoglu’s Narrative

Acemoglu has vividly described his beliefs about automation in Power and Progress (P&P). The book may contain one of the strongest cases against automation available today, and the viewpoint it presents is decidedly not mainstream. The narrative presented in P&P is that automation has already proven to cause wage stagnation while promoting inequality through the erosion of labor’s share of national income.

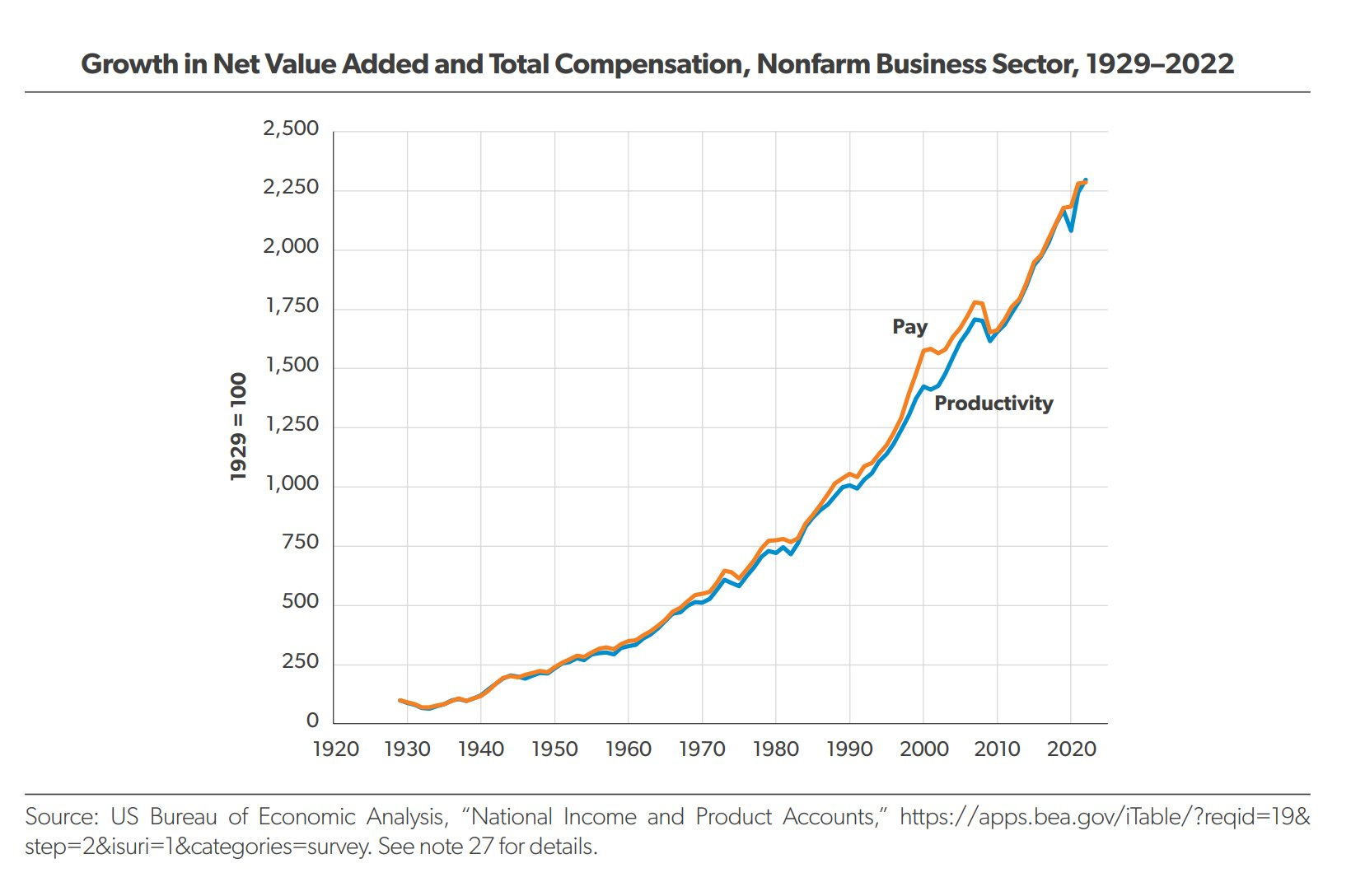

This narrative is problematic for a few reasons, including that pay and productivity have not come apart:1

Another problem is that the labor share has not eroded much, and also, that the capital share has eroded relatively more than the labor share!

It may seem unintuitive that both capital and labor can explain declining shares of national income while the tax share remains constant, but this is because of the growth of the residual share, which indicates an increasing amount of pure profit, driven by markups and declines in the natural rate of interest.2

P&P’s case that automation has already immiserated society, driven inequality, and made workers worse off is based on surprisingly thin evidence.3 So, what does the evidence say?4

Labor-Saving Technology in Review

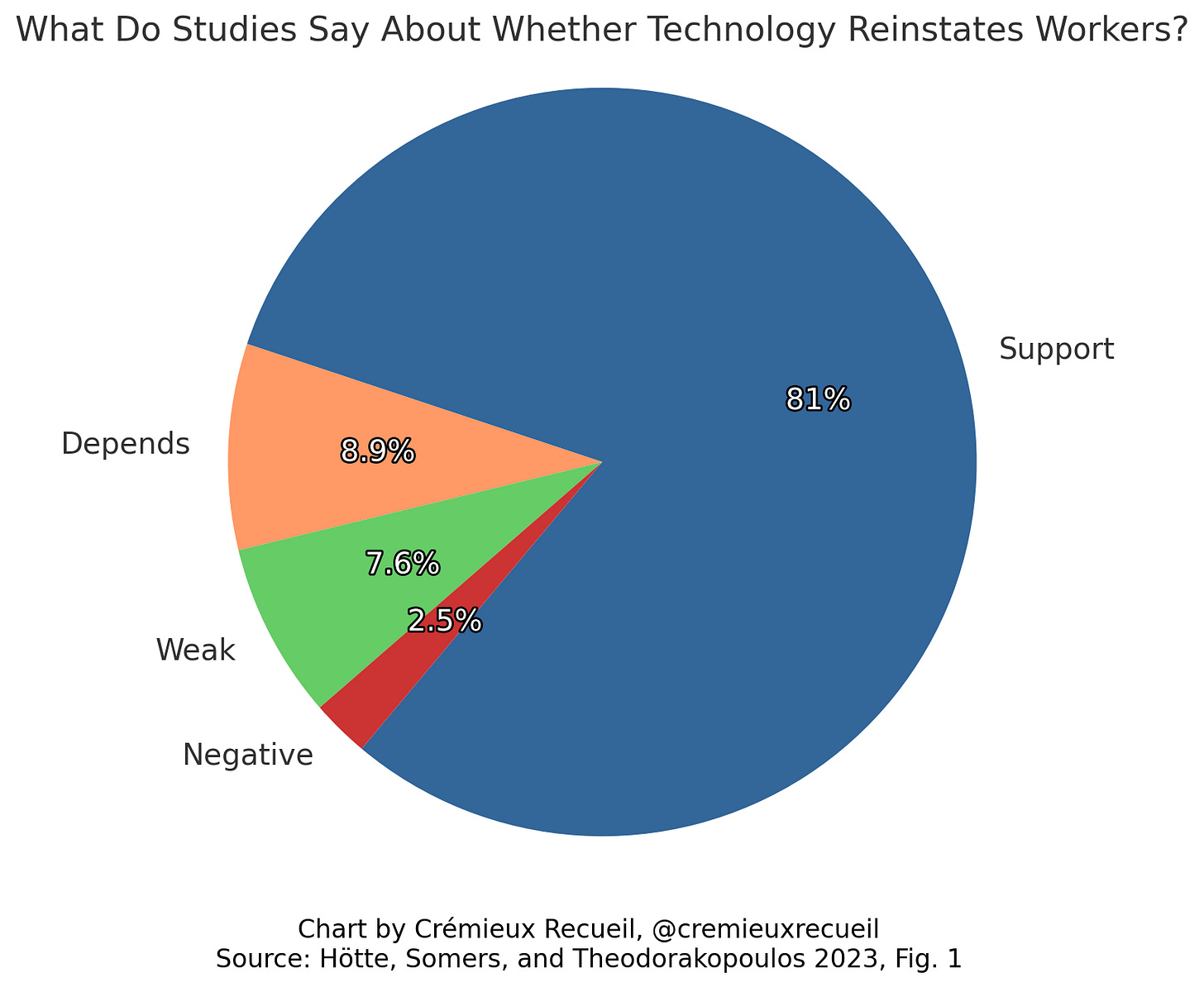

In late 2023, Hötte, Somers and Theodorakopoulos performed a systematic literature review on the topic of how technological change affects employment. They classified results according to the type of evidence they presented across four categories:

Statistically significant and supportive findings (Support, Positive)

Conditionally significant and supportive findings (Depends)

Statistically significant findings with weak, negligible magnitude-effects (Weak)

Studies with nonsignificant or opposite effects (Negative)

One of their first questions was how many papers supported the idea that technological change replaced affected workers’ roles—replacement. In general, studies do tend to conclude that new technology—as opponents of automation have suggested—replaces workers:

While most studies do suggest that labor-saving technology replaces workers, this needs to be further broken down, to see whether the effect differs across ICT, robots, innovations, TFP-style, or other types of technologies. As the table below shows, across 111 estimates, there’s not a lot of heterogeneity outside of innovations:

This seems open-and-shut: studies agree, labor-saving technology replaces workers! But that’s not all there is to this. When technology replaces workers, it does so by saving costs and potentially increasing productivity, ultimately stimulating the demand for labor. To that end, we should also expect technology to reinstate workers. Across 79 studies, there’s overwhelming agreement about the existence of a reinstatement effect:

If we break this down across technology types like we did with replacement, we end up with this table based on 87 estimates:

This may seem reassuring, but it’s not quite yet until we know about two more things. The first of these things is whether the introduction of technology boosts real incomes. We have that result ready, with data from 33 studies:

This result is similar to the rest: new technology does, overall, boost real incomes. If we break this down across types of new technologies, we see a now-familiar result based on 34 estimates:

The second thing we have to worry about, though, is how replacement and reinstatement come together to affect net employment. Across 89 studies, we get the most ambiguous set of findings yet:

And if we break this down across 95 estimates for different technology types, we get a clearer picture for some types than for others:

The results from the introduction of ICT and TFP-style technology change suggest that employment tends to change from production- to service-oriented, and increase accordingly. For the introduction of robots, changes to net employment tend to be highly ambiguous, and overall negligible. This is the clearest example where technology replaces labor, and it is not a clear example where that labor remains displaced.5 Robot studies tended to show:

a clear displacement effect for occupations with relatively low skill requirements, blue-collar occupations, as well as routine manual occupations. Blanas et al. (2019) additionally documented a negative employment effect for middle-skill workers. In contrast, Dekle (2020) found that the introduction of robots increased the demand for high school graduates. Most of these studies also found that high-skill or more qualified workers experienced employment gains in response to a rising robot exposure, and faced a lower risk of job loss or pay cut. Graetz and Michaels (2018) showed that the reduced demand for low-skill labor is fully offset by higher demand for skilled labor. Only Acemoglu and Restrepo (2020) found no support for the reinstatement effect in high-skill jobs.

To wrap this up, a few findings stand out:

Technology displaces labor and increases the demand for labor, and this tends to have negligible effects on net employment.

There’s more displacement for low-skilled, production, and manufacturing work.

There’s not much reason to think blue collar workers will remain displaced.

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

The Present Future, Japan

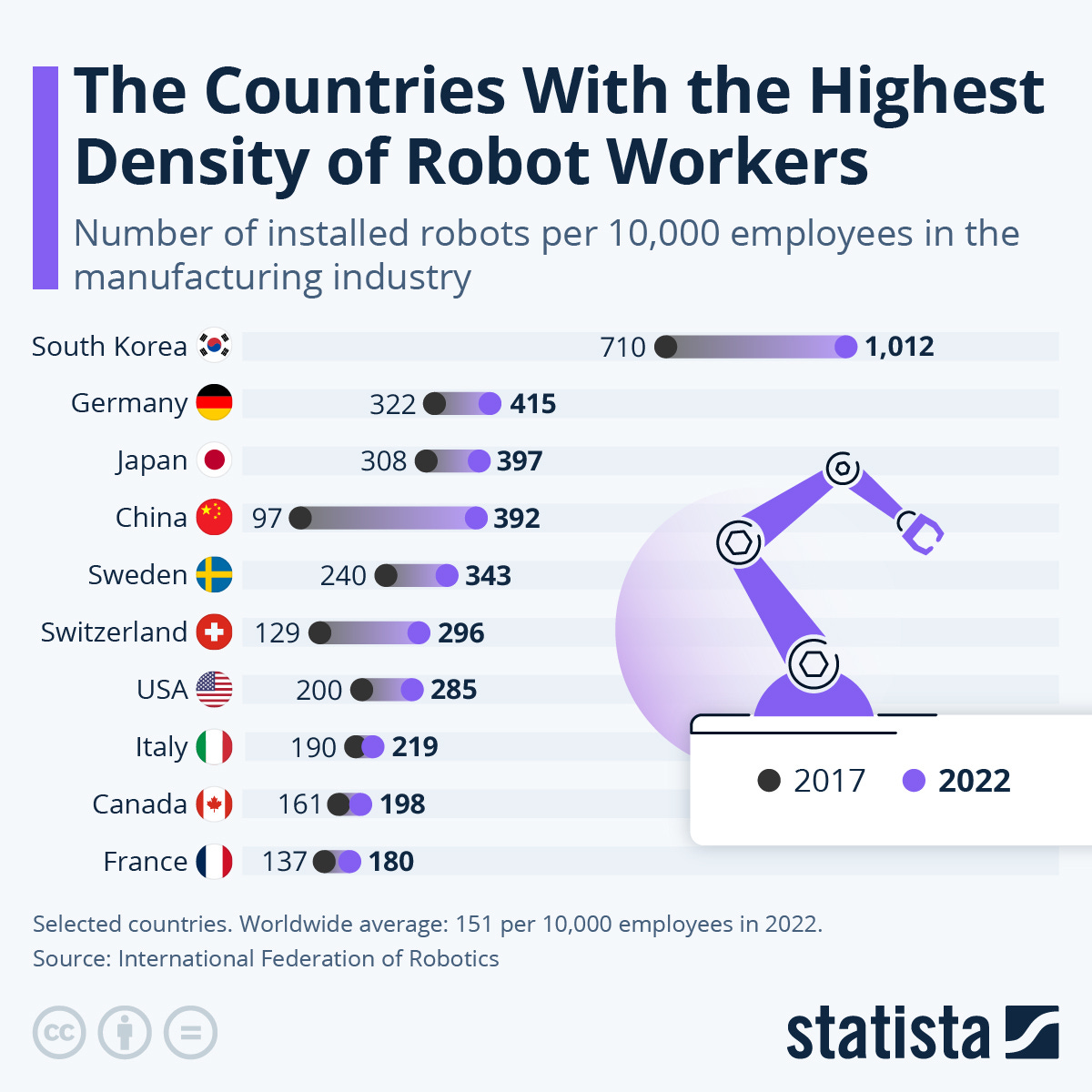

There are several nations outcompeting the U.S. when it comes to industrial robot installation. See if you notice anything special about them.6

Notice Sweden. The prevailing opinion there is generally more amenable to automation than it is in America. This was evocatively stated in a New York Times profile on automation in 2017:

“In Sweden, if you ask a union leader, ‘Are you afraid of new technology?’ they will answer, ‘No, I’m afraid of old technology,’” says the Swedish minister for employment and integration, Ylva Johansson. “The jobs disappear, and then we train people for new jobs. We won’t protect jobs. But we will protect workers.”

Automation boosts Swedish productivity, and being open to automation makes that possible. Part of the Swedish openness to automation probably comes from Swedes feeling secure in their employment and their quality of life, due to their culture, their laws, and their employment arrangements.

Though Swedes may be more accepting of robots than Americans, the impacts of robots on outcomes like wages aren’t obviously dissimilar between the two countries, or between Europe and America more generally (see Footnote 4). But the situation in Japan seems to actually be different. For starters, Japan’s labor market is weird. Lots of Japanese employees are employed in the same firms—but not necessarily the same jobs—for life. Accordingly, an interview in Nikkei said the following:

Japanese managers are enthusiastic about technological innovation and, in addition, since Japanese firms adopt life-long employment, labor unions are open to automation or labor-saving technology that improve the work environment. In the western countries, labor unions are typically organized by occupation: thus, for example, transferring a lathe operator to another occupation is very difficult.

The same paper that quote is in also said that

Without the fear of job loss, labor unions actually welcomed the introduction of robots at production sites because robots release union members from difficult tasks. For instance, KHI describes the impact of the Kawasaki-Unimate 2000, one of the first robot brands in Japan, as follows: “The unmanned production line capable of spot welding 320 joints per minute took over the work of 10 experienced welders. Including day and night shifts, it saved the labor of 20 people and as a result, the use of such highly versatile robots freed workers from welding, one of Japan’s so-called ‘3K’ (kitsui, or ‘hard’; kitanai, or ‘dirty’; and kiken, or ‘dangerous’) jobs.” While the number of shop floor workers involved in spot welding tasks was reduced, these workers were released from the hardship associated with these tasks.

When the authors interviewed Japanese manufacturers about why they adopted robots, they unanimously agreed on two things: that the reason for Japan’s early and dramatic level of robot adoption was Japan’s peculiar employment practices, and that robots did not cause job loss.

Empirical assessment of Japan’s experience with automation has borne out the views of these interviewees. In one case, it was found that declining robot prices led to increased robot purchasing, and then to higher employment via increased productivity in industries that adopted those robots. In another case, a researcher found… basically the same thing:

Robots have raised the productivity of Japanese industries, helped lower costs, raised average industry wages, and helped sustain the global market shares of Japanese corporations. This has allowed the aggregate demand for Japanese labor to be higher than otherwise.

Perhaps we might see Japan as a model, but Japan is weird, so perhaps not. Emulating Japan might entail compromise in other ways, and it’s certainly the case that America would be worse off if, for example, it had Japan’s low service sector productivity, even if emulating Japan boosted American manufacturing prowess.

Regardless of which models work well, what Japan really offers us is an important confirmation that automation does not inherently deprive people of work. This is good: update if you haven’t already!

America’s Automated Future

A better model for America may be America… and Singapore.

Though America has shown a lot of pushback against the adoption of automation technologies, it has engaged in automation, and that has effects that people have endeavored to understand. Here’s a relevant map, showing robot exposure by county:

Compare that map to this map showing Americans’ exposure to offshoring:

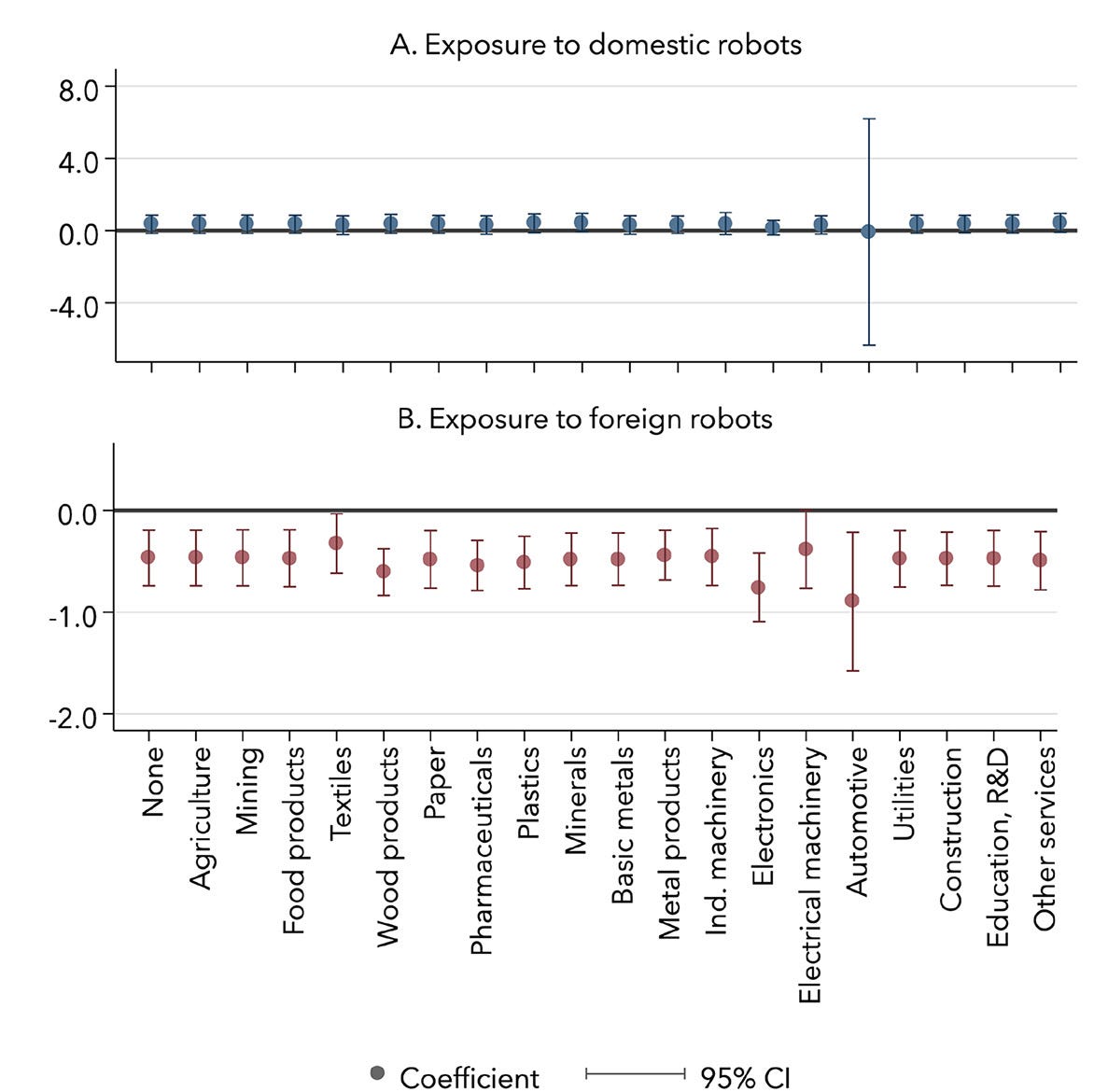

Offshoring—moving business operations to other countries—is a reviled practice in the U.S., and robots might help with it. Bonfiglioni et al. assessed the impact of robot exposure on employment in manufacturing and everything else, and they found this:

Total employment wasn’t really affected, but manufacturing employment went down. Nonmanufacturing employment compensated for the loss, and overall, wages might have been slightly boosted, with ambiguous effects in manufacturing and benefits outside of manufacturing.

But these results conceal an interesting dynamic: industrial robots displace American workers in manufacturing, yes, but much less so in areas with high exposure to offshoring. Industrial robots actually reduce the incidence of offshoring, and their harmful effects on manufacturing employment are concentrated in jobs involving tasks that are not offshorable.

Another way to get at the reshoring and anti-offshoring impact of robots is to look at what happens to employment in Mexico when the U.S. adopts robots. The job a robot does in the U.S. ought to displace the jobs done by people in foreign countries that benefit from American offshoring, and that is exactly what happens: when Americans adopt robots, Mexican employment, exports, and export-producing plant numbers decline.

In another study, it was found that each new robot per 1,000 workers was associated with 3.5% more reshoring, with benefits for the wages and employment of professional workers, but not necessarily for workers in “elementary-routine” occupations.7

In effect, industrial robots slow a decline many Americans take issue with, while helping to reverse it in parts, and they promote stateside production while doing so. The attendant benefits to this are considerable, even if people end up having to deal with the hassles of reskilling when a robot directly replaces their current role. For example, this has national security benefits, it can help to provide higher volumes of exports and provide demand for imports that can be used for industrial purposes, potentially supporting ports in the process, and it also encourages domestic agglomeration, and, frankly, it is a benefit that people are pushed out of often-dangerous jobs that machines should be doing and into jobs that are safer and which will also tend to have more room for growth.8 But the main point, for domestic workers, is that automation is not a reason to feel glum; doom is not inevitable, so feeling gloom is eventually wrong, because producing more is good, and even if people are displaced, it’s temporary, and the improved economy makes it possible for people to be reinstated more rapidly than if America’s industry continues to slowly lose blood to offshoring. So, things will get better, just as they did when Singapore reindustrialized.

Singapore’s experience reindustrializing is the experience of automation-led manufacturing revival, from which the country has massively benefitted.

But, Singapore’s manufacturing revival hasn’t enriched the country through direct manufacturing employment. In fact, that’s fallen:

The country got richer and people’s lives became better for the same reasons that hurting manufacturing in a targeted way broadly causes decreases in quality of life: producers spend their money and sell their products, they demand labor, and through their spending, they stimulate other people’s demands for labor, and so on.

But What About AI?

We don’t really have any great reasons to fear manufacturing automation as a society, but eventually, AI might take away all our jobs. At that point, we’ll be dealing with something entirely novel, so it’s OK to have a weaker prior for what that’ll do. But Acemoglu seems to disagree, not with the need to deal with transformative AI, but with the idea that it will be transformative at all. The arguments in his recent paper arguing that were summarized by Maxwell Tabarrok on his blog.

Briefly, Acemoglu created a model that justified his beliefs, and could not have returned surprising results because the results were driven by his assumptions. He assumed, for example, that AI models will only ever be chatbots, which is already untrue. He also assumed that models will be incredibly expensive, which is increasingly untrue for inference and with the advent of foundational models, less true in a much more general sense. Finally, he assumed that AI capabilities progress will stall, which is just something he apparently came up with based on some not-so-relevant RCTs conducted with already-dated models.

Regardless of your thoughts on whether AI will be transformative, you can probably agree that Acemoglu’s exercise dismissing it was not very convincing. And if you’re still thinking about what AI will do, you can look at the results of this recent business survey on AI usage. It found something curious: about a quarter of firms use AI to replace workers tasks, but only a twentieth of them have altered their employment levels due to AI usage. While it might be premature, maybe the situation with AI and employment is similar to the situation with manufacturing automation!

At the end of the day, there’s a simple choice on offer: accept automation and its benefits or America will fall behind its rivals. There is a lot to be gained from automation and, thankfully, a fuller accounting of the research than what was presented in Power and Progress lets us know there’s not much to fear.

With automation in hand, America can stop bleeding and start growing its manufacturing, reindustrialize, and power a new era of domestic growth.

This report shows that there is divergence between aggregate productivity indices and median pay and compensation, but this has more to do with demographic effects on labor markets and rising inequality in productivity rather than directly with automation.

The preprint of this paper contained a chart showing shares over time. The supplement of the paper contains interesting results, like this decomposition of the wealth share, which shows that trends in wealth and capital are not being driven purely by housing:

For a more comprehensive discussion of P&P, see Noah Smith’s review:

It is worth noting that there is some evidence that robots have made wages less responsive to unemployment and that more recent automation efforts might be more labor-displacing than earlier ones.

Additionally, in a meta-analysis of the impacts of robots on wages, the aggregate effect tended to be near-zero and economically negligible. The impacts were similar between the U.S. and Europe, but Japan showed evidence for more positive effects on wages.

In terms of the rate of growth in raw terms, recently, China seems to outshine the rest of the world.

Another study, perhaps not worth mentioning due to relevance, suggested that the intensity of robot use in high-income countries positively impacted foreign direct investment growth in low- and middle-income countries between 2004 and 2015. In a sense that is effectively promote offshoring, because that means people are choosing to build overseas.

For the top-3% of the sample by robot use, automation resulted in less foreign direct investment, consistent with reshoring occurring. For the timeframe of the sample, the level of automation wasn’t as extreme as it often is or could be today, so perhaps more of the occupations that would use robots now would choose to reshore instead of this effective offshoring seen in most—but not the top-3% and increasingly not for another 25%—of the sample.

Very interesting. I'm curious if you could drive a bit deeper into the displacement though. When low skill labor is getting replaced by higher skill labor, how quickly is this seen happening relative to the adoption of increased automation and are the studies tracking whether these are the same people (as in the Japanese model of upskilling existing workers) or something more along the lines of the typical objection that native workers are losing their jobs and then being replaced with immigrants on work visas?

The experience of the Rust Belt with offshoring certainly suggests that traditional economic assumptions that workers will naturally and quickly find other work after being displaced are not necessarily correct. Likewise, the "learn to code" meme (implying that it's easy to transition from lost jobs into new tech jobs) has aged badly, showing both that upskilling is often more difficult than assumed due to mismatches between the qualities demanded by the previous positions and the new positions and the more recent significant cuts in both wages and total employment in many tech positions showing that the pace of change is making it increasingly difficult to even determine what skills displaced workers 'should' be retraining into.

There are concerns that even when the aggregate is neutral or mildly positive, there are severe concentrated losses in certain places and sectors, so it is quite logical for the workers in those to oppose changes that will drastically harm them in return for diffuse mild benefits to a larger number elsewhere.

Similarly, I'm interested in transition choke points regarding the pace of change and numbers displaced. Upskilling has relatively limited pipelines in many cases. How do we measure the available capacity to retrain, identify the productive areas to retrain into, and give workers the signals and resources needed to align themselves into new careers without creating the equivalent of traffic jams in our retraining pipelines?

I'm not an academic (but I am a new paid subscriber!) so I don't read many academic papers. It seems to me that it would require mind reading to come up with an accurate answer to this question. By that I mean:

When a factory automates (or moves overseas) the purpose of doing so is to produce the same or better quality output at a lower unit cost. If a company that takes these steps is alone in its industry in doing so while its competitors operate as before, then, assuming it gets the better quality and lower costs as planned, it will benefit with higher profit margins. However, if competitors also do the same thing with the same results, it is only a matter of time before the now higher margins cause a price war to break out, as smaller players benefit more from gaining market share through discounts than they do by keeping margins high. The price war continues until profit margins for everyone have shrunk to the point where the ROI on new investment is no longer that attractive.

The workers at the automated factory are now more productive and can demand more pay, while the workers whose jobs were shipped overseas are at least temporarily unemployed. But looking at the factories with more robots to count the number and pay of the human employees is missing the point. The fact that the industry after the price war is now selling better products at a lower price than before the automation/offshoring means that its customers can get what they want at a lower price and have money left over.

What do customers do with that money left over? They spend it on something, and it would take mind reading to know what that was. But whatever it is, that will require more employees to provide.

The example I've used is the fact that entry of Chinese manufacturing into world markets in a big way starting in roughly 1990 +/- allowed Americans to save lots of money on what they bought. At the same time there began rapid growth in the number of health clubs, yoga and Pilates studios, etc. Maybe it was a coincidence, but I think the savings on cheap products gave consumers more to spend on personal improvement services. That created big growth in the number of employed personal trainers, yoga instructors, etc.

I'm not saying that a newly unemployed 60 y.o. factory worker in Georgia could move to Denver to teach yoga, just that there was a big jump in the number of employed yoga instructors. I'm not sure how their pay stacked up versus working in a dirty, noisy textile factory, but working conditions were certainly better if nothing else.

But I'm not a mind reader. I can't prove that that is how people spent their money, but they got it from somewhere, and lower consumer prices is a good candidate. Unless these academic studies try to take that into account, they are missing an important part of the effects on employment of automation and offshoring.