Preregistration Is No Panacea

Stopping scientific cheaters requires setting up systems that can't be gamed

This post is brought to you by my sponsor, Warp.

This is the eighth in a series of timed posts. The way these work is that if it takes me more than one hour to complete the post, an applet that I made deletes everything I’ve written so far and I abandon the post. Check out previous examples here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. I placed the advertisement before I started my writing timer.

Apparently thoughts of God make people more accepting of the decisions made by artificial intelligence. That’s the conclusion of a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article that includes a whopping eight experiments with a total of 2,462 participants.

Across the experiments, participants were prompted to think about God in various ways, and doing so resulted in things like reduced reliance on human product recommenders and heightened reliance on AI recommendations, apparently resulting from feelings of smallness and fallibility when God is on the mind, which were moderated by individuals’ initial beliefs in God. In other words, God makes people accept algorithms, with effect sizes for main effects ranging from correlations of about 0.11 to 0.19. A p-curve analysis also suggests that these studies had an average statistical power of… 9%? Some of the p-values for the main effects were also marginally significant—not a good sign.

The conclusion that “God increases acceptance of artificial intelligence in decision-making” does not appear to be on solid ground, but this study had a hallmark of modern, ‘good’ science: preregistration: The authors stated ahead of time which outcomes they would look into. Given they did that, their results should have been credible and more likely to hold up because they didn’t cheat, and we know they didn’t, because they said everything they were going to do before they even got the data. Right?

A Message From My Sponsor

Steve Jobs is quoted as saying, “Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Few B2B SaaS companies take this as seriously as Warp, the payroll and compliance platform used by based founders and startups.

Warp has cut out all the features you don’t need (looking at you, Gusto’s “e-Welcome” card for new employees) and has automated the ones you do: federal, state, and local tax compliance, global contractor payments, and 5-minute onboarding.

In other words, Warp saves you enough time that you’ll stop having the intrusive thoughts suggesting you might actually need to make your first Human Resources hire.

Get started now at joinwarp.com/crem and get a $1,000 Amazon gift card when you run payroll for the first time.

Get Started Now: www.joinwarp.com/crem

From Preregistration to Non-Replication

The initial study was published in early August 2023, and a replication of the subset of experiments that could be replicated online was underway shortly after December 8th.

By July of 2024, the replication was published. This replication was, like the original article, preregistered. It also followed the designs used in the original article, and instead of a total sample of 1,531, it had 4,143 participants. This replication effort was much better powered, and it produced markedly different results:

None of the effects held up: all of them became so small they could be safely ignored, ranging from 0.002 to 0.03. Not shown, there was also a failed replication with a negative effect size (-0.10), but that result was nonsignificant (p = 0.077), and there was a sort-of replication, but it came from an experiment with a confusing typographical error and the result was marginally significant (0.09, p = 0.024).

In other words, a preregistered study failed to replicate. This should not happen if you believe in the power of limiting analytical flexibility through preregistration, and yet, it did.

Or maybe it didn’t! The original set of studies wasn’t high-powered enough to deliver credible results, but maybe the result was right anyway. The original authors replied to the replication, suggesting two explanations.

Maybe the population’s “AI attitudes” shifted immediately after the original article came out due to interim increased exposure to AI-generated content, rendering their conclusions no longer correct, but still, at the time, correct.

Maybe the manipulation used in the replication was less effective than when they did it.

For the first option, it sounds like coping with contradiction. If it’s true, then their findings meant something but now they might not. Maybe they’ll be relevant to less AI-exposed populations for a while, but only a while. If the authors refashioned this into an argument about sampling differences, they would probably be throwing their own data under the bus because they didn’t sample better and further concern about sampling indicts them due to their smaller sample size.

For the second option, if true, then unless the first option was or has become right, replication should still be possible. But I doubt that’s it. The justification provided for the second option ended up being a bunch of just-nonsignificant or marginally significant tests that felt random and seemed cherrypicked to support the idea that their work was valid and this replication wasn’t a threat to it.

An unexplored third option the original authors could have engaged in would have been to cast doubt on the moral character of at least one of the authors of the replication study. This could actually work, because the second author on the replication article was recently revealed to be someone who had committed scientific fraud, perhaps unwittingly. For background, she has also spent a lot of time attacking scientific fraud since it was revealed that one of her colleagues (Francesca Gino) engaged in it, but she still admits she engaged in the QRP ‘excluding data to obtain a desired result’, which most people (appropriately, in my opinion) see as tantamount to fraud. Make of this what you will. I wouldn’t have respected the argument, but I could see someone making it, and I could see it being right.

Why Didn’t Preregistration Work?

Preregistration without high levels of detail probably doesn’t mean much. People often deviate from their preregistered protocols, and deviations frequently favor observing the findings authors desired. The protocols registered by the initial article and by the replication were both AsPredicted preregistrations, and if you click into them, you’ll see that they both lacked sufficient detail to constrain their authors’ actions. Or in other words, though they nominally preregistered an analysis plan, they were still free to gather and analyze the data in ways they had no formal obligation to disclose.

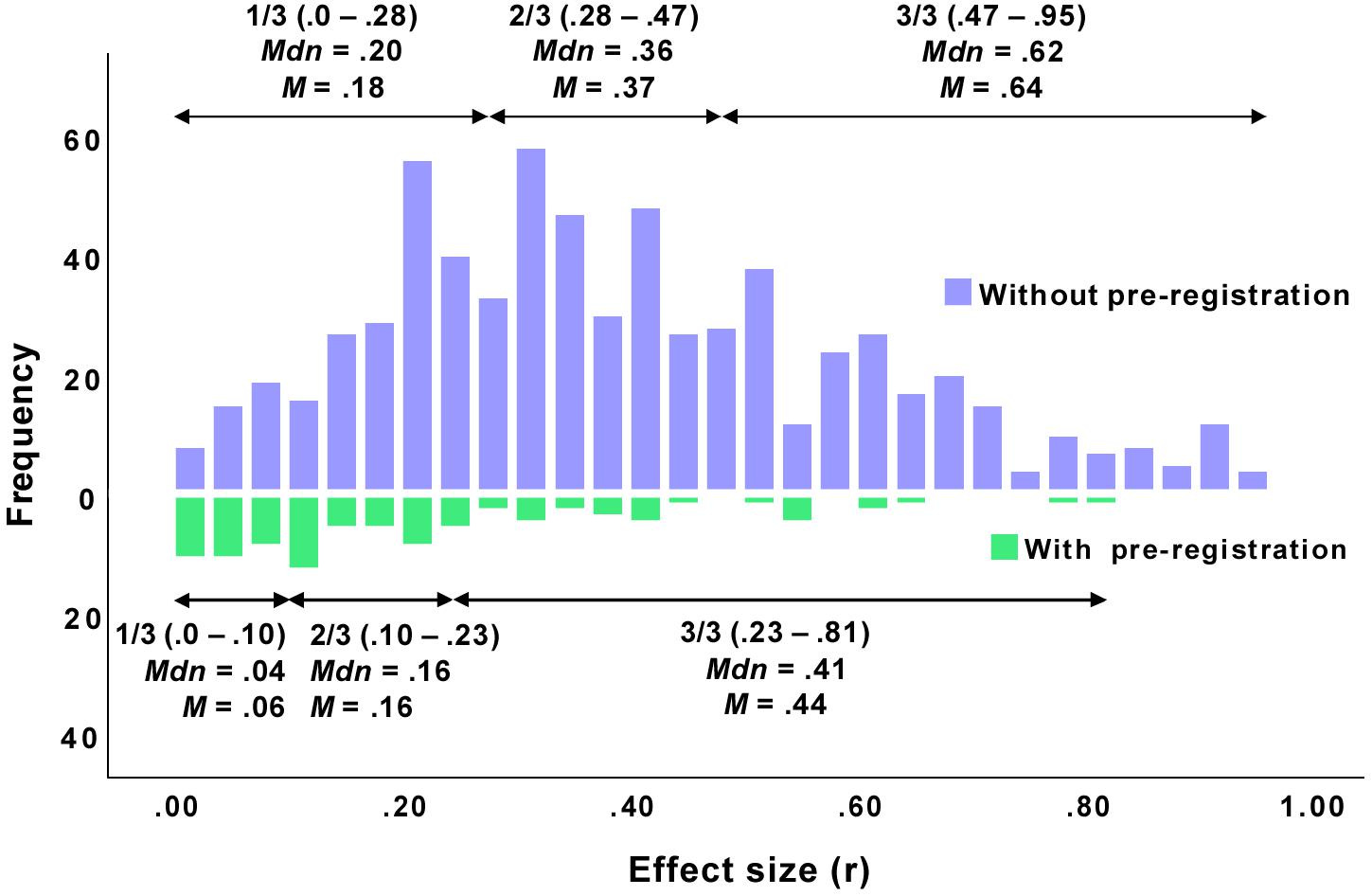

There’s some evidence that this is true. For example, in psychology, the effect sizes from preregistered papers are generally much smaller than the effect sizes in non-preregistered research:

The distribution of p-values in preregistered clinical trials is also substantially less suspect than it is in the sample of clinical trials that aren’t preregistered:1

But in economics rather than medicine, the supposed protective effects of preregistration are far less apparent:

It’s hard to say if preregistration makes things better, because it’s generally not mandated, so preregistering is liable to be selective, both with respect to the authors who preregister and the hypotheses that end up being preregistered. Regardless, any preregistration will probably tend to be better than no preregistration, and mandating preregistration would probably be an improvement, but in some cases, preregistered study data will still be subjected to enough abuse to end up like having no preregistration at all.

This concern is known, and methods to reduce it have been developed. One of these is the registered report. In a registered report, peer review and publication acceptance or rejection take place before the results of a study are known. Regardless of the result, the article gets published, so there’s no selection on significance for publication reasons, only for reasons having to do with authors aiming for personally desired results.

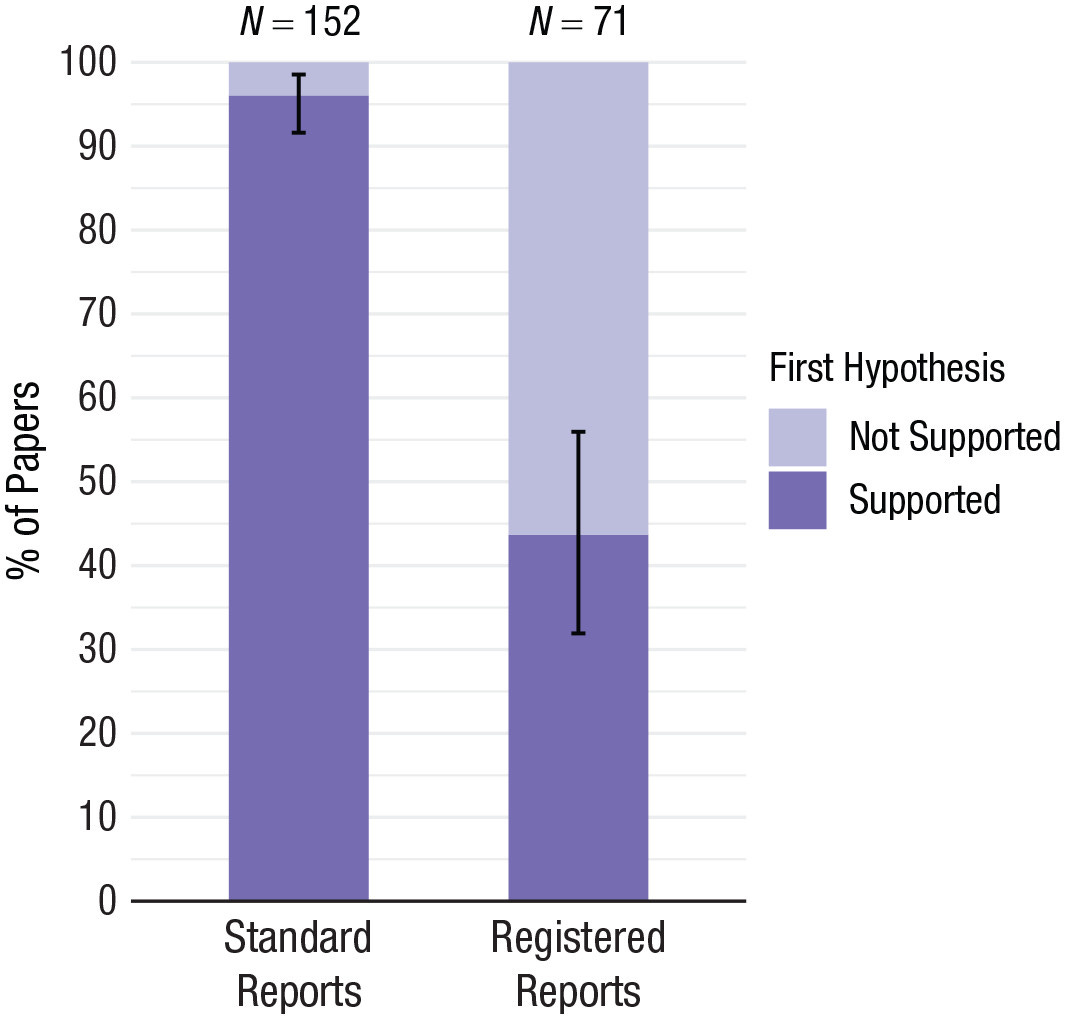

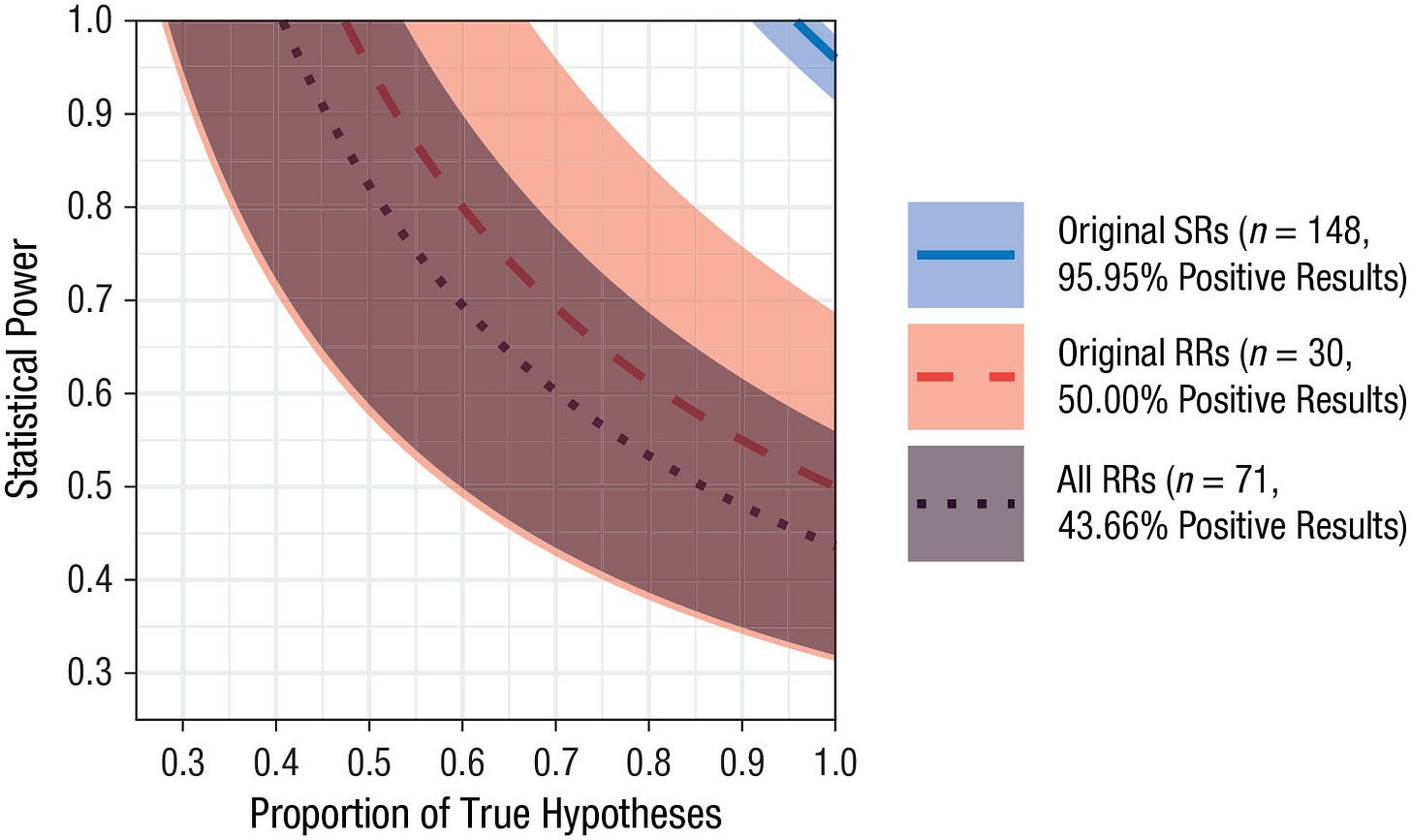

When registered reports are compared to standard reports, they fare amazingly well. Registered reports appear more credible than standard reports because they are vastly more likely to report results that do not favor the paper’s hypothesis, results which are not positive. That suggests they’re not hacked together to confirm something biased. Standard reports, in contrast, look to produce too many positive results to be believable.

The reason standard reports’ positive result rate looks so unbelievable is simple: if their record accurately reflects reality, then they must have more than 90% power to test more than 90% true hypotheses. Since they tend to have low power—and indeed, lower power than registered reports—and the replication crisis has proven researchers aren’t actually that good at selecting true hypotheses to test, this is highly unlikely, and it seems highly likely that the results of registered reports hew much closer to reality.

But like preregistrations in general, maybe the benefits of registered reports are overstated due to selection of authors into doing them, selection of hypotheses into being tested in registered reports, a bias against positive results by those doing them, and so on.2 Registered reports are newer and there’s not much data on how well they work to prevent issues, so I’m not yet convinced they’re the fix preregistration needed. From reading a few, I feel reasonable certain that they often still leave too much analytical flexibility in the hands of authors. With that said, my tentative summary of why preregistration alone and maybe even registered reports might not work is that there’s not enough strictness.

What Can We Do?

My suggestion to make preregistrations work like they should for promoting scientific credibility is to make science much more akin to the pipeline endorsed by the U.K.-based Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) and the U.S.-based National Center for Educational Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE). These organizations fund studies of educational interventions that are viewed as being likely to work and they have strict criteria for evaluation. Their criteria are so strict, in fact, that they might be enough to ensure whatever they do manage to find is credible.

For starters, the EEF and NCEE fund interventions that have evidence behind them, and they fund them being done in realistic settings with sizable samples, meaning that before any analysis is done, they’re already extensively vetted both the ideas and the scenarios interventions will take place in. The EEF and NCEE really want to find educational interventions that work, and it shows. But the big requirement that makes the EEF and NCEE so good is that they have authors strictly specify how their interventions are to be run and evaluated, and they have people who are not the proposers of those interventions do the evaluations. They take all of the researcher degrees of freedom out of the hands of the original researchers and place them in the hands of evaluators whose sole purpose is doing what was prespecified to be done, and they mandate that all results be reported, so there’s nothing missing from the literature they help to fund.

The EEF/NCEE pipeline for research avoids major theoretical issues with interventions, avoids generalizability threats, and avoids analytical flexibility, leaving behind a residue of high-quality investment and evaluation. To what end? Finding very small effect sizes, that’s what end.

There’s no p-hacking, no dubious excess of results just over or under critical p-value thresholds, and most effects are estimated with a high degree of precision, implying that the studies are, as expected, relatively high-powered, and the mean effect size is a piddling 0.06 standard deviations in size. This is what you should expect from a combination of ‘vetted for likelihood of working’, ‘sampled well’, ‘entirely preregistered’, ‘independently evaluated by experts’, and ‘reported whether researchers like the result or not’. The result is not very impressive in effect size terms, but it’s honest, and it’s the standard more fields should strive for. More fields should move beyond preregistrations to something much stricter, such as this.3

Not Enough

Even if you do science extremely well and preregistration advocates start pushing for rigorous, large-scale, preregistered and independently evaluated studies, it’s unlikely that they’ll ‘fix science’ in a deeper sense. Even if every result becomes replicable because studies are all conducted reasonably and evaluated well, many studies will still be worthless. Consider this recent quotation found in The Atlantic:

Business-school psychologists are scholars, but they aren’t shooting for a Nobel Prize. Their research doesn’t typically aim to solve a social problem; it won’t be curing anyone’s disease. It doesn’t even seem to have much influence on business practices, and it certainly hasn’t shaped the nation’s commerce.

If this research doesn’t actually accomplish anything or affect the day-to-day operations of people in business… what’s the point? A likely point is personal enrichment:

Still, its flashy findings come with clear rewards: consulting gigs and speakers’ fees, not to mention lavish academic incomes. Starting salaries at business schools can be $240,000 a year—double what they are at campus psychology departments.

Plenty of academics are in similar situations, where they’re working on topics that simply do not matter. Whether thinking about God increases people’s acceptance of algorithmic decisions is one of those topics: regardless of the result, it doesn’t affect anyone’s life or lead to any changes in the real world. This is why preregistration will not save science: it cannot force researchers to work on things that matter.

This is a concern a lot of people have. If you’ve been following the development of the Department of Government Efficiency, you might’ve seen that some of their focus is on allegedly bad research, like this:

This grant is misdescribed, both in the amount, and in what the goal of the research was. If I were in charge of grant allocation at the NIH, I probably would have given this grant out, even if I were tasked with fighting waste. The reason I would issue this grant is that the real underlying research the image describes can help to inform us about steroid impacts on behavior and it involved a proposal to use credible designs to do just that. But if someone really were just trying to “watch hamsters fight on steroids” without any real goal, I would recommend the grant be denied.

But what about4

Watching flies have sex

Giving massages to rats

Figuring out why jellyfish glow

Monitoring penguin poop with satellites

Bottling the blood of horseshoe crabs5?

All of these things sound dubious at first pass, but they all ended up being great ideas.

Watching flies have sex gave us screwworm elimination, providing us with a lot more living farm animals, billions in annual savings, and considerable cheaper meat. Giving rats massages led to massage therapy for premature infants in NICUs, saving newborn lives. Without exploring the jellyfish’s glow, we wouldn’t have found green fluorescent protein, a key tool for understanding protein mobility and interactions. Tracking penguin poop led to discovering more than a million penguins and motivated satellite tech development used in hundreds of other domains. And horseshoe crab blood? Without it, you wouldn’t have clean medicine, vaccines, and other injectables, because the blue blood of horseshoe crabs has been extensively and critically used for ages now in the detection of contaminants.

It can be extremely hard to say what research is good ahead of time. It’s clear that tons of research is not good, but what’s left behind after eliminating obviously bad research is not just good research. So my suggestion—primarily for the soft sciences—is simple: focus on predictive rather than explanatory research.

The idea that thinking about God increases one’s acceptance of algorithms is kind of nutty. It’s not inspired by any outside theory, findings, or real-world observation, it’s just something that pops in your head one day, and you go out and test it if you’ve got a grant available or you can convince someone to cut you a check for your useless idea. That research is positing and ostensibly (but not really) explaining something pointless; it comes from and goes to nowhere, and much of social science is like it, because the concepts being investigated are often borne from whole cloth, and humans aren’t good at making up social and psychological quantities to investigate that are, coincidentally, real.

Predictive social science, on the other hand, justifies its existence through being able to tell you about the future. A focus on predictive questions and predictive models creates findings that are useful in their own right—this is the point of a lot of industrial-organizational psychology—in addition to ploughing fertile ground to develop theories from. For social questions, there may not be a ‘glowing jellyfish’ that needs to be explained, but if someone discovers that they can, say, predict a person’s social position with a handful of easily measured, non-obviously associated variables, then they might just have a jellyfish to explain. Additionally, focusing on prediction means that research is inherently robust, because if you cannot predict things, you never found anything in the first place, and surely no one considers it acceptable to train but not test a model—and yet that’s what explanatory research does all the time, without saying it.

Picking prediction over explaining the loosely or simply atheoretical would also help to prevent stupidity in science for other reasons. One is that hypotheses have to be reformulated into predictive language, and that precludes doing things that inherently cannot be validated by making them obvious.6 Another is that for a predictive study to be a success, you obviously have to end up being able to predict things, so you would need to be talking about findings that are sufficiently strong, rather than too weak to hold up with reasonable repeated sampling. In other words, if you discover that you cannot carve nature at its joints, this methodological paradigm won’t suit you.

If you’re a fan of prediction markets, then you probably think that preregistration and a focus on predictive science dovetail well. I feel the same way, and if support for this approach wins out, we’ll quickly discover that a career in science just doesn’t suit people who aren’t ready to try their hand at predicting what happens next.

Another interesting finding from this study is that the p-values are only suspicious for primary outcomes. Evidently no one is p-hacking or selecting on significance for secondary outcomes! This replicates the result found by Gorajek and Malin, who showed p-hacking for tests involving focal variables, but not for those involving control variables. For another fun, relevant result, see this work by Brodeur, Cook and Heyes.

One possibility is that registered reports are more likely to be replication studies, and those are more likely to be negative, perhaps because they might target unlikely work to see if it holds up. Removing replication studies didn’t change the results of the analysis of registered versus standard reports:

As expected, replications were much more common among RRs (41 / 71 = 57.75%) than SRs (4 / 152 = 2.63%), and replication RRs had a descriptively lower positive result rate than original RRs (see Table 1). However, this finding fails to explain the main result described above: When analyzing only original articles, the difference between the positive result rates of RRs and SRs, −45.95%, was still significantly smaller than zero, χ2(1) = 46.28, p < .001, and not statistically equivalent to a range between −6% and 6% (z = 4.31, p > .999), both at α = 5%.

Another proposal is to have co-authors who do not participate in the original writing and evaluation steps of a paper but who, instead, come in as a “red team” that attacks the paper before it goes live, trying to find and poke at every possible hole before the paper goes out to the public. You can find an example of this—that also includes prediction market inputs about the results of the paper—here.

This idea comes from someone whose Twitter post quickly popped out of my feed. If you can find them, tell me who they are and I’ll link them here.

This is not to say that, for example, economists should not deal with natural experiments or quasi-experiments. Those are generally fine, because the relevant situations to study are identified theoretically.

Yes! "Training a model without testing it" is exactly what so much social science research amounts to. Plotting the marginal "fitted values," i.e., predictions, of a model as a function of some feature to make some point about what has been learned from the data, but without ever actually, you know, testing the model's predictions out-of-sample.

This article is imo entirely correct on methods, but I also want to talk about how to improve the chosen topics.

Back when physics was in its infancy, it started with quantifying things that people have already noticed. For example, gravity. People had already noticed that things tend to fall down, rather than up, or the movements of celestial bodies. The hard part was generating a specific formula on how it works in-detail. Only *after* considerable hard work we found that intuitions on at least some points were wrong, such as that the force of gravity is actually identical between differently-weighted objects. But many if not most intuitions turned out roughly correct! Likewise for many other things; The basic motivating question for many researchers was extremely often "why is this thing, which we all can perceive and all agree on, the way it is?". This does not preclude eventually overturning some intuitions, but that is generally much further down the line!

In social sciences however, I regularly see even honest students and researchers start from the assumption that all "folk theories" are wrong and they only try to work out how they are wrong. Upturning intuitions is their entire raison d'etre. If you don't get "surprising" results, you're at best boring and uncool or at worst vilified. Best example is imo stereotypes; If I ask friends who literally studied psychology, many will declare with confidence that all stereotypes are wrong and have been thoroughly debunked by psychological research. Yet stereotype accuracy is one of the most robust and replicable findings there is. But psychologists shouldn't stop there! We need to quantify how accurate they are, we need to find how different parameters influence accuracy, and so on. The good news is, this is at least being worked on by a small group of researchers; The bad news is, many others try their best to entirely ignore these findings.

To be frank, you can't do science this way. You should start from the things that regular society can broadly agree on AND which is backed up by replicable, strong findings- stereotype accuracy, the primacy of selection effects in education, the robustness of intelligence measures, and so on. From there, you can work yourself towards more contentious, variable or difficult topics. But you shouldn't start from those.

This avoids another problem we could see here: If you start out with investigating the things that most people have been agreeing on for a long time, an argument like "maybe attitudes changed, dunno" will seem non-credible. And this is very good, since we definitely shouldn't waste money on findings that very plausibly won't last even just a few years.